While a novice in the Dominican convent at Naples, Bruno removed images of the saints from his cell, keeping only a crucifix. He also expressed doubts about the devotion to the Virgin Mary, actions that drew early suspicion of unorthodoxy.

On Ash Wednesday, 17 February 1600, Giordano Bruno was led to the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome to face execution. Condemned by the Roman Inquisition for heresy after seven years of imprisonment, he was stripped naked and bound to a stake. His tongue was gagged, preventing him from addressing the crowd that gathered to witness his death. A crucifix was offered to him, which he refused. The pyre was then lit, and flames consumed him. Thus perished one of the most fascinating and unyielding minds of the 16th century.

Giordano Bruno lived at a crossroads between the waning traditions of Renaissance scholasticism and the dawning horizons of modern science. From his position, he sought to reconcile the Hermetic and magical philosophies of the Renaissance with the new cosmology ushered in by Copernicus. A fearless and uncompromising thinker, he remained indifferent to the hostility his ideas provoked and steadfast in his refusal to conform to the boundaries imposed upon thought.

Although Bruno is sometimes portrayed as having been condemned for his scientific views, most historians agree that his trial and execution resulted primarily from theological charges, including denial of central Catholic doctrines such as the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, and the virginity of Mary. His cosmological speculations on multiple worlds and an infinite universe were not the formal grounds for his condemnation. Today, Bruno is remembered for both his execution at the hands of the Inquisition and his wide-ranging ideas, which combined Renaissance magic and Hermetic traditions with bold philosophical reflections that anticipated aspects of modern thought.

Giordano Bruno was not primarily a figure in the history of science, but a symbol of intellectual freedom and the consequences of opposing the Inquisition. While he is sometimes associated with heliocentrism, this is a misconception. The idea that the Earth moves was proposed long before Bruno. In the 5th century BCE, the Greek philosopher Philolaus hypothesized that the Earth was a sphere revolving daily around a central fire. Later, Aristarchus of Samos identified this central fire as the Sun. However, these early heliocentric models were incomplete, and they could not explain certain observational questions, such as why the stars appeared fixed in the night sky if the Earth was in motion.

In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy proposed the geocentric model, placing the Earth at the center of the universe with all celestial bodies revolving around it. This model dominated European thought for approximately 1,400 years. In 1444, Nicholas of Cusa challenged the geocentric assumption. Still, it was not until 1543, with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri VI (Six Books Concerning the Revolutions of the Heavenly Orbs), that the heliocentric system was coherently articulated.

The heliocentric system was later supported and popularized by Galileo Galilei, whose telescopic observations provided evidence for Copernican astronomy and led to his trial before the Inquisition in 1633.

Before Galileo, Giordano Bruno also advocated for the Copernican system. Unlike Copernicus, however, Bruno integrated heliocentrism into a broader cosmology and theology, which included ideas about an infinite universe and multiple worlds. His theological views challenged certain core doctrines of the Church, particularly regarding the truth-value of Christ, which contributed to his condemnation.

Renaissance Man and Rebel Monk

Pulsating life in Naples’ Piazza San Domenico Maggiore, before the Benedictine church, as depicted by 19th-century German artist Oswald Achenbach.

Born in 1548 in Nola, near Naples, Bruno was educated at the Augustinian Monastery in Naples and attended public lectures at the Studium Generale. At 17, he joined the Dominican Order at the Monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples and adopted the name Giordano. Some sources suggest he chose this name after his metaphysics tutor, Giordano Crispo, while others believe it was in honor of Saint Jordan of Saxony, following Dominican tradition.

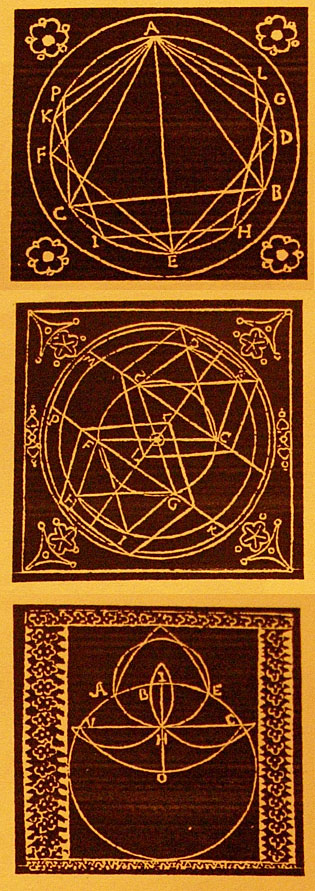

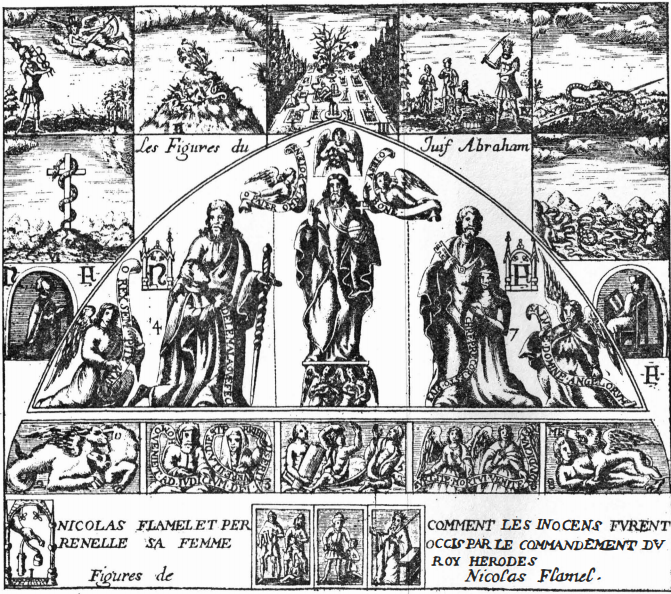

Three memory seals or “mnemonic devices” by Giordano Bruno, based on classical techniques, prominent in Western Hermetics and alchemy.

At the age of 24, Bruno was ordained a priest and became known for his remarkable skill with the art of memory. He even traveled to Rome to demonstrate his mnemonic system before Pope Pius V and Cardinal Scipione Rebiba. Bruno’s reputation grew not only because of his memory skills but also because of his thinking and interest in ideas that were considered heretical.

These beliefs, including his defense of controversial theological positions, led the Church to prepare charges against him. Learning of this, Bruno fled Naples, abandoned his religious habit, and was no longer recognized as a priest.

For the next 15 years, Bruno traveled widely across Europe, moving from city to city. In 1579, he arrived in Geneva, where he published a controversial critique that led to his brief arrest along with the printer. He refused to recant and continued to defend his work.

He later moved to France and was elected to lecture in philosophy. His extraordinary memory attracted wide attention, with some contemporaries believing it to be nearly supernatural. His reputation eventually reached King Henry III, who summoned him to court. Bruno later recalled:

“I got me such a name that King Henry III summoned me one day to discover from me if the memory which I possessed was natural or acquired by magic art. I satisfied him that it did not come from sorcery but from organized knowledge, and, following this, I got a book on memory printed, entitled The Shadows of Ideas, which I dedicated to His Majesty. Forthwith, he gave me an Extraordinary Lectureship with a salary.”

Under the patronage of King Henry III of France, Bruno published several works based on his mnemonic models of organized knowledge, including De umbris idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas, 1582), Ars Memoriae (The Art of Memory, 1582), and Cantus Circaeus (Circe’s Song, 1582).

With letters of recommendation from Henry III, Bruno traveled to England in April 1583 as a guest of the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. In England, he associated with the Hermetic circle around John Dee and lectured at Oxford, but he was unsuccessful in obtaining a formal teaching position, partly due to resistance from university authorities, including George Abbot, later Archbishop of Canterbury. Contemporary accounts suggest that Abbot mocked Bruno’s support of Copernican heliocentrism.

During this period, Bruno also published several Italian dialogues and cosmological works, including La Cena de le Ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper, 1584), which provoked controversy. His outspoken and tactless manner sometimes led to a loss of support from influential patrons.

From 1585 to 1592, Bruno traveled through Germany, lecturing and producing works on magic, including De Magia (On Magic), Theses De Magia (Theses on Magic), and De Vinculis in Genere (A General Account of Bonding).

In 1591, Bruno received an invitation from Venetian patrician Giovanni Mocenigo to instruct him in the art of memory. Mocenigo also suggested that Bruno could apply for the vacant chair of mathematics at the University of Padua. Seeking opportunities in Venice, one of the more liberal Italian states, Bruno returned to Italy.

He first traveled to Padua, but his application for the mathematics chair was unsuccessful. The position was awarded to Galileo Galilei in 1592. In March 1592, Bruno moved in with Mocenigo in Venice, but the patron soon became alarmed by Bruno’s heterodox views. On May 22, 1592, Mocenigo denounced Bruno to the Venetian Inquisition, leading to his arrest. Bruno was charged with heresy, blasphemy, and personal misconduct, including his belief in the plurality of worlds.

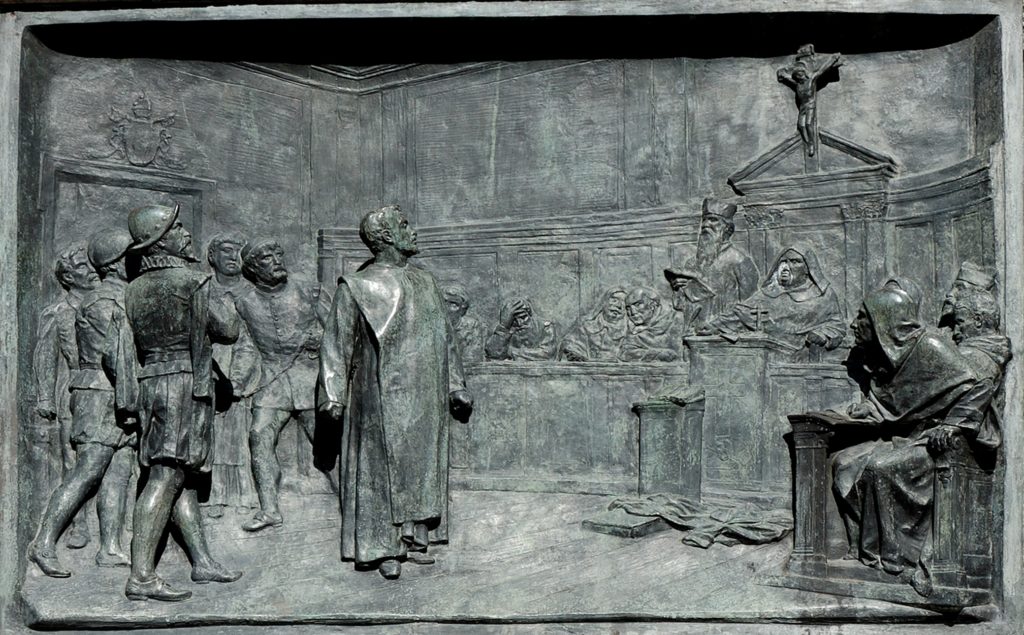

Bronze relief by Ettore Ferrari at Campo de’ Fiori, commemorating Giordano Bruno’s trial before the Roman Inquisition.

The Burning of Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno’s trial by the Roman Inquisition lasted approximately seven years, during which he was held in confinement. The charges against him included heresy, blasphemy, and immoral conduct. Some accounts, including that of Giovanni Mocenigo, suggest that Bruno’s blunt manner, such as reportedly criticizing Church rituals, aggravated the perception of his offenses:

“I have sometimes heard Giordano say in my house that no religion pleases him. He has shown that he plans to make himself the creator of a new sect under the name of ‘new philosophy’ and has said that our Catholic faith is full of blasphemies against the majesty of God, and that it is time to remove the discussion and the income from friars, because they defile the world, that they are all asses, and that our opinions are the doctrine of asses, that we have no proof that our faith has any merit with God, and that he marvels at how many heresies God tolerates among Catholics.”

According to Luigi Firpo, the Roman Inquisition charged Bruno with:

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and speaking against it and its ministers;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about the Trinity, divinity of Christ, and Incarnation;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith pertaining to Jesus as Christ;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith regarding the virginity of Mary, mother of Jesus;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about both Transubstantiation and Mass;

- claiming the existence of a plurality of worlds and their eternity;

- believing in metempsychosis and in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes;

- dealing in magics and divination.

Bruno refused to recant his beliefs. On January 20, 1600, Pope Clement VIII declared him a heretic, and the Inquisition sentenced him to death. Reportedly, Bruno responded:

“Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it.”

On Ash Wednesday, February 17, 1600, Bruno was burnt at the stake. Church records describe the execution:

(Bruno) “was led by officers of the law to Campo de’ Fiori, and there, stripped naked and tied to the stake, he was burnt alive, always accompanied by our company singing the litanies, and the comforters, up to the last, urging him to abandon his obstinacy, with which he ended his miserable and unhappy life.”

Giordano Bruno’s statue in Campo de’ Fiori was erected in 1889 by sculptor Ettore Ferrari, Grand Master of the Italian Freemasons. Unveiled on the site of his execution, it was a Freemason response to Pope Leo XIII’s 1894 condemnation of masonry. The inscription reads: “To Bruno – From the Age He Predicted – Here Where the Fire Burned.”

Bruno’s entire works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1603. Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, who had been involved in Bruno’s trial by the Roman Inquisition, was deeply aware of the political and intellectual implications of executing a thinker whose ideas had reached monarchs, dukes, and ambassadors across Europe. His experience with Bruno influenced the Church’s later approach to handling challenges posed by new scientific ideas, including the case of Galileo Galilei decades later. A later account summarizes the connection between the two cases:

“In the same rooms where Giordano Bruno was questioned, for the same important reasons of the relationship between science and faith, at the dawning of the new astronomy and at the decline of Aristotle’s philosophy, sixteen years later, Cardinal Bellarmino, who then contested Bruno’s heretical theses, summoned Galileo Galilei, who also faced a famous inquisitorial trial, which, luckily for him, ended with a simple abjuration.”

The Nolan Philosophy

Giordano Bruno was not executed for supporting the Copernican heliocentric system. The Catholic Church did not officially declare heliocentrism heretical until the trial of Galileo Galilei, when it was judged to contradict Scripture. Before that, the Church had treated Copernicus’s ideas with caution and scrutiny, but there was no formal doctrinal opposition. Copernicus’s work initially received Church approval. It was only later that the Church reversed its position.

Bruno was instead condemned for theological and philosophical views considered heretical, including denying the divinity of Christ, questioning the Trinity, and proposing ideas such as “the Holy Spirit as the soul of the world.” In other words, he challenged orthodox Christology and central Catholic doctrines.

Bruno was strongly influenced by Renaissance Hermeticism and Neoplatonism, and he developed a unique philosophical system sometimes called Nolan philosophy, after his hometown, Nola. His concept of infinite worlds was inspired by Copernicus’ heliocentric model, which he extended philosophically. Bruno argued for an infinite universe with countless solar systems, potentially inhabited by other beings, challenging the traditional cosmology of his time.

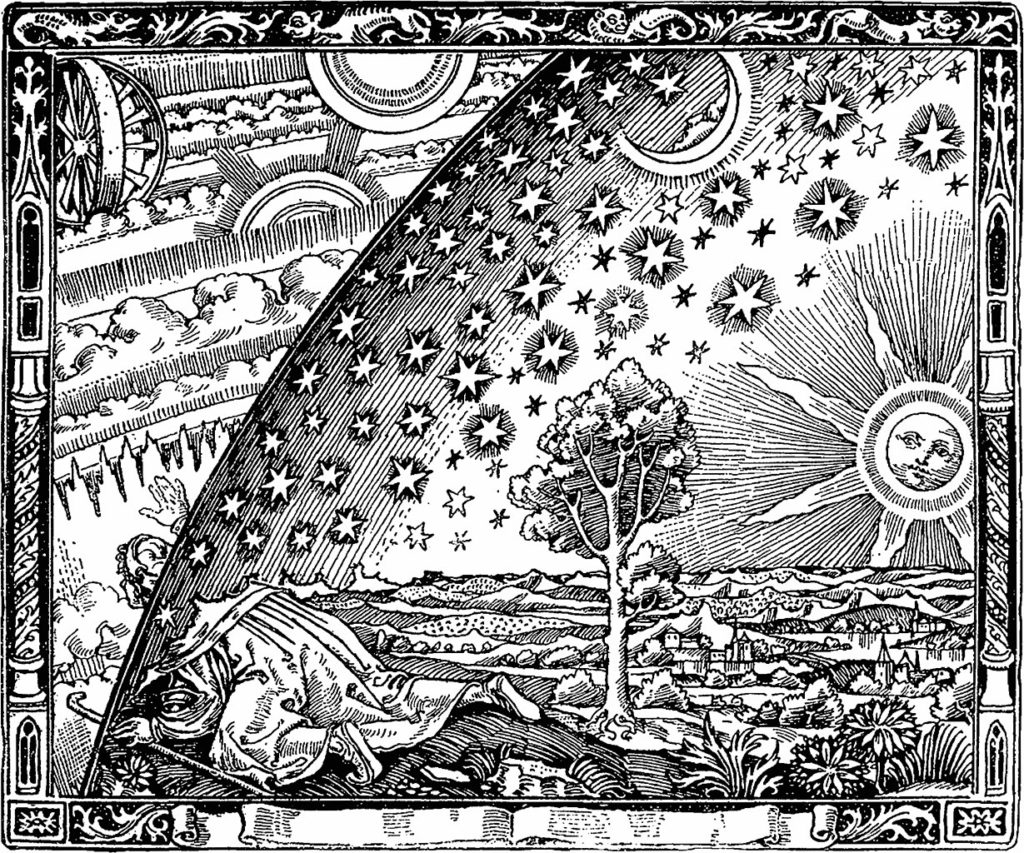

1888 engraving from Camille Flammarion’s “L’atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire”, showing a flat Earth and heavenly spheres. Caption: “A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch…”

The four elements depicted in one of Giordano Bruno’s mnemonic devices.

Bruno envisioned the universe as infinite, homogeneous, and isotropic, without a central point. He proposed that stars were like the Sun, each potentially surrounded by their own planets, and that the universe could contain an infinite number of such solar systems. Bruno accepted the classical four elements—earth, water, air, and fire—as constituting all matter and rejected the Aristotelian idea of a separate celestial quintessence. He also argued that space and time are infinite, a view that challenged traditional Christian notions of a finite Creation.

Bruno described the cosmos poetically, emphasizing its infinitude and the abundance of worlds:

“Whatever is an element of the infinite must be infinite also; hence both Earths and Suns are infinite in number. But the infinity of the former, is not greater than of the latter; nor where all are inhabited, are the inhabitants in greater proportion to the infinite than the stars themselves.”

From his cosmological speculations, Bruno developed a pantheistic vision, seeing God as present throughout the universe, in all beings and heavenly bodies. This perspective conflicted with orthodox Christology, as it implied that divine presence was universal and not mediated solely through Christ, raising theological questions about the truth-value of Christ.

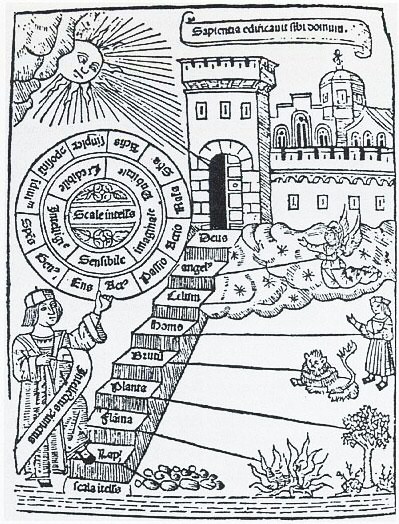

Scala Naturae by Raimundus Lullus, depicting the hierarchy of being. Unlike orthodox clerical versions, Hermetic thinkers saw these levels as grades of perfection, with humans able to ascend or descend.

In Bruno’s cosmology, the universe was infinite and boundless, lacking a top, bottom, center, beginning, or end. This conception dismissed the idea of a God located “at the top” overseeing Creation in a hierarchical sense. For Bruno, however, this did not negate God. Rather, it implied a divine presence immanent throughout the cosmos, accessible to all things at all times. This view challenged the traditional Scala Naturae (Great Chain of Being), which placed God as the fixed apex of a hierarchical universe. In De Magia, Bruno describes two directional scales within the cosmos: a descending scale, reflecting the emanation of divine influence, and an ascending scale, representing the return of created beings toward the divine, emphasizing a dynamic rather than strictly hierarchical order.

- Descending scale: “In all the panorama before our eyes, God acts on the gods; the gods act on the celestial or astral bodies, which are divine bodies; these act on the spirits who reside in and control the stars, one of which is the earth; the spirits act on the elements, the elements on the compounds, the compounds on the senses; the senses on the soul, and the soul on the whole animal.”

- Ascending scale: “From the animal through the soul to the senses, through the senses to compounds, through compounds to the elements, through these to spirits, through the spirits in the elements to those in the stars, through these to the incorporeal gods who have an ethereal substance or body, through them to the soul of the world or the spirit of the universe; and through that to the contemplation of the one, most simple, best, greatest, incorporeal, absolute and self-sufficient being.”

The Great Chain of Being (1579) from “Rhetorica Christiana” by Franciscan Diego de Valadés, depicting a God-given hierarchical order, in contrast to Ramon Llull’s more flexible version.

Bruno used the Greek myth of Actaeon to illustrate the pursuit of divine truth. In the myth, Actaeon hunts a stag with his dogs in a forest and unexpectedly comes upon the goddess Diana bathing. Struck by her divine beauty, he gazes upon her and is transformed into a stag himself. His own hounds then hunt and kill him.

For Bruno, Actaeon’s transformation symbolizes the seeker’s encounter with the divine. The divine truth is both the goal and the transformative force. The prey Actaeon pursues represents the divine, and in glimpsing it, he is transformed into that which he seeks. The hounds, interpreted as the will and discursive intellect, consume him, symbolizing the challenges inherent in comprehending and integrating divine knowledge. As Bruno explained in The Heroic Enthusiasts:

“…the ultimate and final end of this sport, is to arrive at the acquisition of that fugitive and wild body, so that the thief becomes the thing stolen, the hunter becomes the thing hunted; in all other kinds of sport, for special things, the hunter possesses himself of those things, absorbing them with the mouth of his own intelligence; but in that Divine and universal one, he comes to understand to such an extent, that he becomes of necessity included, absorbed, united. Whence, from common, ordinary, civil, and popular, he becomes wild, like a stag, an inhabitant of the woods; he lives god-like under that grandeur of the forest; he lives in the simple chambers of the cavernous mountains, whence he beholds the great rivers; he vegetates intact and pure from ordinary greed, where the speech of the Divine converses more freely, to which so many men have aspired who longed to taste the Divine life while upon earth, and who with one voice have said: Ecce, elongavi fugiens, et mansi in solitudine. Thus the dogs—thoughts of Divine things—devour Actæon, making him dead to the vulgar and the crowd, loosened from the knots of perturbation of the senses, free from the fleshly prison of matter, whence they no longer see their Diana as thro.”

For Bruno, the active pursuit of a desired object transforms the seeker, such that in striving toward the divine, the seeker becomes aligned with that which is sought. This employs the concept of Eros as mystical love, in which the exchange of phantasmatic images impresses the spirits of the subjects and the objects. Through mystical love, the interaction between the spiritual impressions of subject and object creates a reciprocal transformation

This concept reflects Bruno’s naturalistic pantheism and his view of the cosmos. In his hierarchy of being, God, as pure actuality, descends, while Nature, as pure potentiality, ascends. Where they meet, coincidentia oppositorum occurs, or the unity of opposites, an idea which Bruno drew from Nicholas of Cusa, though its philosophical roots can be traced to Heraclitus. Because Bruno conceived the universe as infinite, with the divine immanent in all things and all things reflecting the divine, this unity of opposites is not limited to a single point but occurs throughout the cosmos.

Bruno also draws on another idea from Nicholas of Cusa, with roots traceable to Empedocles: “God is an infinite circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” From this arises the notion that the constant unity of opposites in an infinite universe constitutes the very state of being. Because the divine is immanent in nature and nature reflects the divine, and because there is no permanent apex in the cosmic hierarchy, a separate creator is unnecessary. The anima mundi generates forms intrinsically. Creation is both self-originating and self-sustaining.

For Bruno, to understand the divine is to understand nature. By grasping the laws of the universe and exercising the intellect in concert with mystical love, one aligns with the cosmos. As the intellect internalizes these natural laws, the heroic enthusiast emerges, just like Actaeon. In this framework, there is no need for a mediator, such as Christ, between the natural and the divine.

In Bruno’s philosophy, mystical love is the active force that bonds finite creatures in an infinite universe. It is the same principle illustrated in the myth of Actaeon: the seeker gazes upon the divine, and in that encounter, the seeker and the sought are transformed into one another. Mystical love is the medium through which the intellect and the will engage with the world, allowing the binder and the bound, the manipulator and the manipulated, to participate in a reciprocal exchange of forces and images.

“A bonding agent does not unite a soul to himself unless he has captured it; it is not captured unless it has been bound; he does not bind it unless he has joined himself to it; he is not joined to it unless he has approached it; he has not approached it unless he has moved; he does not move unless he is attracted; he is not attracted until after he has been inclined towards or turned away; he is not inclined towards unless he desires or wants; he does not desire unless he knows; he does not know unless the object contained in a species or an image is presented to the eyes or to the ears or to the gaze of an internal sense.”

Bonding agents must understand the laws of nature, which include Bruno’s vision of the elements: gods consist of pure fire, airy and watery spirits are denser and made of air and fire, and terrestrial spirits, being the densest, are composed of water, air, and fire. Effective binding requires knowing what resonates with these spirits and the elements that compose them.

“Therefore, he who knows how to bind needs to have an understanding of all things, or at least of the nature, inclination, habits, uses, and purposes of the particular things that he is to bind.”

While a bonding agent is not always a magician, a magician is always a bonding agent. In his De Magia, Bruno identifies several meanings for magic and magician:

- Wise man: “For example, the Trismegistes among the Egyptians, the druids among the Gauls, the gymnosophists among the Indians, the cabalists among the Hebrews, the magi among the Persians (who were followers of Zoroaster), the sophists among the Greeks, and the wise men among the Latins.”

- Magician: “Someone who does wondrous things merely by manipulating active and passive powers, as occurs in chemistry, medicine, and such fields; this is commonly called natural magic.”

- Prestidigitation: “(The type of) magic involves circumstances such that the actions of nature or of a higher intelligence occur in such a way as to excite wonderment by their appearances.”

- Natural magic: “Magic (that) refers to what happens as a result of the powers of attraction and repulsion between things, for example, the pushes, motions, and attractions due to magnets and such things, when all these actions are due not to active and passive qualities but rather to the spirit or soul existing in things.”

- Mathematical magic or occult philosophy: “The use of words, chants, calculations of numbers, and times, images, figures, symbols, characters, or letters. This is a form of magic which is intermediate between the natural and the preternatural or the supernatural.”

- Theurgy: “Prayers, dedications, incensings, sacrifices, resolutions, and ceremonies directed to the gods, demons, and heroes. Sometimes, this is done for the purpose of contacting a spirit itself to become its vessel and instrument in order to appear wise, although this wisdom can be easily removed, together with the spirit, by means of a drug. This is the magic of the hopeless, who become the vessels of evil demons, which they seek through their notorious art. On the other hand, this is sometimes done to command and control lower demons with the authority of higher demonic spirits, by honouring and entreating the latter while restricting the former with oaths and petitions.”

- Necromancy or Pythian magic: “The petition or invocation, not of the demons and heroes themselves, but through them, to call upon the souls of dead humans, in order to predict and know absent and future events, by taking their cadavers or parts thereof to some oracle. This type of magic, both in its subject matter and in its purpose, is called necromancy. If the body is not present, but the oracle is beseeched by invoking the spirit residing in its viscera with very active incantations, then this type of magic is properly called Pythian.”

- Wicked or poisonous magic: “Incantations are associated with a person’s physical parts in any sense; garments, excrement, remnants, footprints, and anything which is believed to have made some contact with the person. In that case, and if they are used to untie, fasten, or weaken, then this constitutes the type of magic called wicked, if it leads to evil. If it leads to good, it is to be counted among the medicines belonging to a certain method and type of medical practice. If it leads to final destruction and death, then it is called poisonous magic.”

- Diviners: “Those who are able, for any reason, to predict distant and future events are said to be magicians. These are generally called diviners because of their purpose. The primary groups of such magicians use either the four material principles, fire, air, water, and earth, and they are thus called pyromancers, hydromancers, and geomancers, or they use the three objects of knowledge, the natural, mathematical, and divine. There are also various other types of prophecy. For augerers, soothsayers, and other such people make predictions from an inspection of natural or physical things. Geomancers make predictions in their own way by inspecting mathematical objects like numbers, letters, and certain lines and figures, and also from the appearance, light, and location of the planets and similar objects. Still others make predictions by using divine things, like sacred names, coincidental locations, brief calculations, and persevering circumstances. In our day, these latter people are not called magicians, since, for us, the word ‘magic’ sounds bad and has an unworthy connotation. So this is not called magic but prophecy.”

- Any foolish evil-doer: “Magic and magician have a pejorative connotation which has not been included or examined in the above meanings. In this sense, a magician is any foolish evil-doer who is endowed with the power of helping or harming someone by means of a communication with, or even a pact with, a foul devil.”

Bruno’s Legacy in Modern Esotericism

Engraving of Giordano Bruno by Johann Georg Mentzel (1677-1743)

Giordano Bruno explored an infinite universe, the unity of opposites, and the immanence of the divine in all things. His ideas challenged traditional hierarchies and orthodox Christian doctrine, ultimately leading to his condemnation and execution by the Roman Inquisition.

In the centuries since, Bruno’s philosophy has been invoked by a wide range of thinkers and movements, from scientists and philosophers to esoteric traditions, each drawing selectively on aspects of his thought. Bruno himself did not advocate allegiance to any particular movement. His writings reflect a pursuit of knowledge, mystical insight, and intellectual freedom.

Yet, Bruno was included as a Gnostic saint in Liber XV, the Gnostic Mass, by Aleister Crowley. He drew on Bruno’s philosophical concepts, including that of mystical love, as part of his own system of Thelema. While Crowley popularized these ideas for a modern magical context, the concepts themselves were already explored in depth by Bruno and others centuries earlier.

Bruno’s legacy is significant in modern esotericism. His integration of cosmology, philosophy, and mystical thought continues to influence Western traditions, showing how Renaissance inquiry laid the groundwork for intellectual and spiritual experimentation.

www.theoldcraft.com

Ralph Edsell | May 30, 2020

|

Love your essay about Giordano Bruno. I am a researcher living in southern California

Sincerely, Ralph