Foxes are often seen as witty tricksters, clever enough to outsmart both friend and foe. Photo: Flickr.

Once upon a time, a crocodile begged a Brahman to carry him to Benares so he might live in the sacred waters of the Ganges. Compassionate, the Brahman agreed, placed the crocodile in his bag, and carried it to the river. But just as he was about to release it, the crocodile seized him, intent on devouring the very man who had helped it.

The Brahman accused the crocodile of ingratitude, but the crocodile replied that nature and custom allowed it to eat the hand that had sustained it. Desperate, the Brahman demanded judgment from three impartial arbiters.

They asked a mango tree, which answered that humans repay kindness with destruction. They eat its fruit, rest in its shade, and then uproot it. They asked an old cow, who replied that humans abandoned her once she was no longer useful, leaving her to die. Both seemed to side with the crocodile.

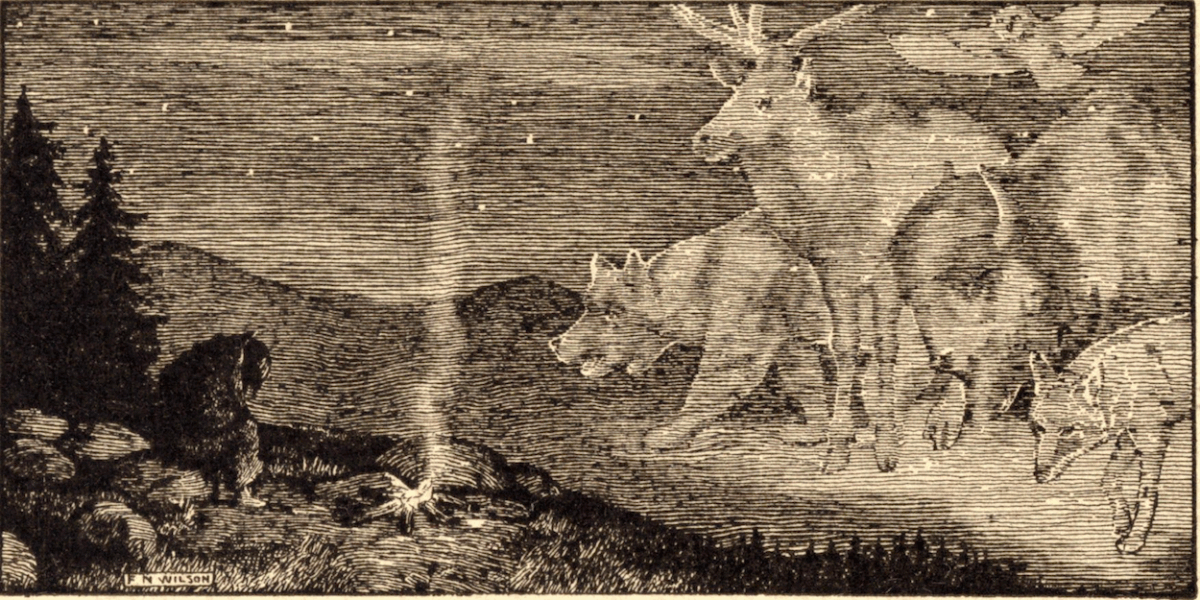

At last, they turned to a fox. The fox appeared to lean toward the crocodile’s argument, but before rendering judgment, he asked to see how the two had traveled together. Eager to prove his point, the crocodile crawled back into the bag. At that moment, the Brahman, prompted by the fox, struck it dead with a stone, and the fox ate it up.

The Indian story of The Crocodile, the Brahman, and the Fox is a lesson that virtue alone cannot protect you. In a world where ingratitude is common, survival often depends on intelligence and adaptability. The fox is a divine trickster that embodies this practical wisdom. It unsettles the moral order, but also saves it when appeals to fairness fail.

The Trickster Fox

Tricksters cross boundaries and cause disruptions that reveal hidden truths. They survive by wit, not force, and they teach through paradox. Sometimes by guiding, sometimes by deceiving. Both the natural and symbolic behaviour of the fox illustrate this ambivalence.

In Romanian ethnographic accounts, the fox approaches households strategically. Even if the gate is open and no dog is near, it does not rush. Instead, it observes and “studies” the household from a distance before moving forward. Its prudence and strategic prowling have thus made it a living metaphor for cunning intelligence.

Such is reflected in language. The English idiom “clever as a fox” praises quick-wittedness and the ability to “outfox” one’s rivals. Meanwhile, Romanian folk wisdom offers a more morally ambivalent reflection in the saying: “A woman is like the fox. She laughs with the dog and steals your chickens.” Here, the fox is feminized and becomes a metaphor for charming duplicity, which can be considered a commentary not only on the animal’s reputation but on social perceptions of wit, gender, and mistrust.

The Fox as a Psychopomp

The Japanese Kitsune, a divine messenger of Inari, is often depicted with red votive bibs (yodarekake), symbolizing the deity and serving as offerings to forge a bond with the god. Photo: Flickr.

Due to its nocturnal activity and liminal nature, the fox is also considered a being of the Otherworld, and thus often functions as a psychopomp, who guides the soul through transitional states. In variants of the Romanian Song of the Dawn, which is sung by mourners before the funeral, the soul of the deceased is told the following:

“Before you go,

Pay heed,

For the fox will surely

Come to meet you.

Stretch out your hand,

Take hers kindly,

For she knows the ways

Of all the forests

And all the waters.”

Here, the fox is not a deceiver but a benevolent psychopomp, a companion who knows the hidden paths through the Otherworld. While a trickster in this world, the fox becomes a guide in the Other.

Ally of Humanity

In the Sumerian myth of Enki and Ninhursag, the two gods work together to make the land of Dilmun fertile and abundant. However, Enki upsets the natural balance through his uncontrolled desires. After several unions with goddesses descended from his own relationship with Ninhursag, his seed is planted in the earth by the goddess herself, and from it grow eight sacred plants. Ninhursag then withdraws from him in anger, and Enki becomes gravely ill.

Then, a fox strikes a bargain with Enki’s brother Enlil, promising to help restore him. In return, Enlil agrees to honor the fox and to erect two birch trees for it in his city. True to its word, the fox retrieves Ninhursag, who cures Enki, thus creating eight minor deities from his ailing body parts. In this myth, the fox is cosmically indispensable, a negotiator between gods who ensures the renewal of life.

Fox (detail) in the Rochester Bestiary, (1230–1300s, England). Digital image: British Library

Throughout European folklore, foxes appear as cunning and clever figures who can outwit stronger opponents and who, just like in the Sumerian myth, are outstanding negotiators. However, in medieval Europe, the fox became a symbol of the devil. Early bestiaries, drawing from the Physiologus (2nd century AD), described the fox as deceptive, never running straight, feigning death, and then striking its prey. Christian writers used this as an allegory to show that just as the devil pretends to be harmless to the unfaithful, the fox lures in victims with trickery before destroying them.

In East Asian folklore and mythology, foxes are revered as powerful spirit-beings who can sometimes shapeshift into humans, such as the Chinese húli jīng, the Korean kumiho, and the Japanese kitsune. According to Yōkai folklore, the kitsune shapeshifts into human form to trick or test humans, or to become their friend, lover, or wife.

Kitsune is also a rain spirit and messenger of Inari, the kami of foxes, fertility, rice, tea, sake, agriculture, prosperity, success, and one of the main kami of Shinto. It is said that the more tails a kitsune has, the older, wiser, and more powerful they are. A kitsune can grow up to nine tails, which is when they become almost a deity, and traditionally, they are worshiped as one.

The Nine-Tailed Kitsune is also the inspiration behind the Kyūbi no Yōko or Kurama, in Naruto. This Nine-Tailed Demon Fox is the most powerful of the bijū, the tailed beasts, which are great manifestations of unlimited chakra. The manga illustrates kitsune folklore quite beautifully, showing how, despite its amazing power and morals that surpass human understanding, the Spirit of the Fox becomes even greater in serving humanity.

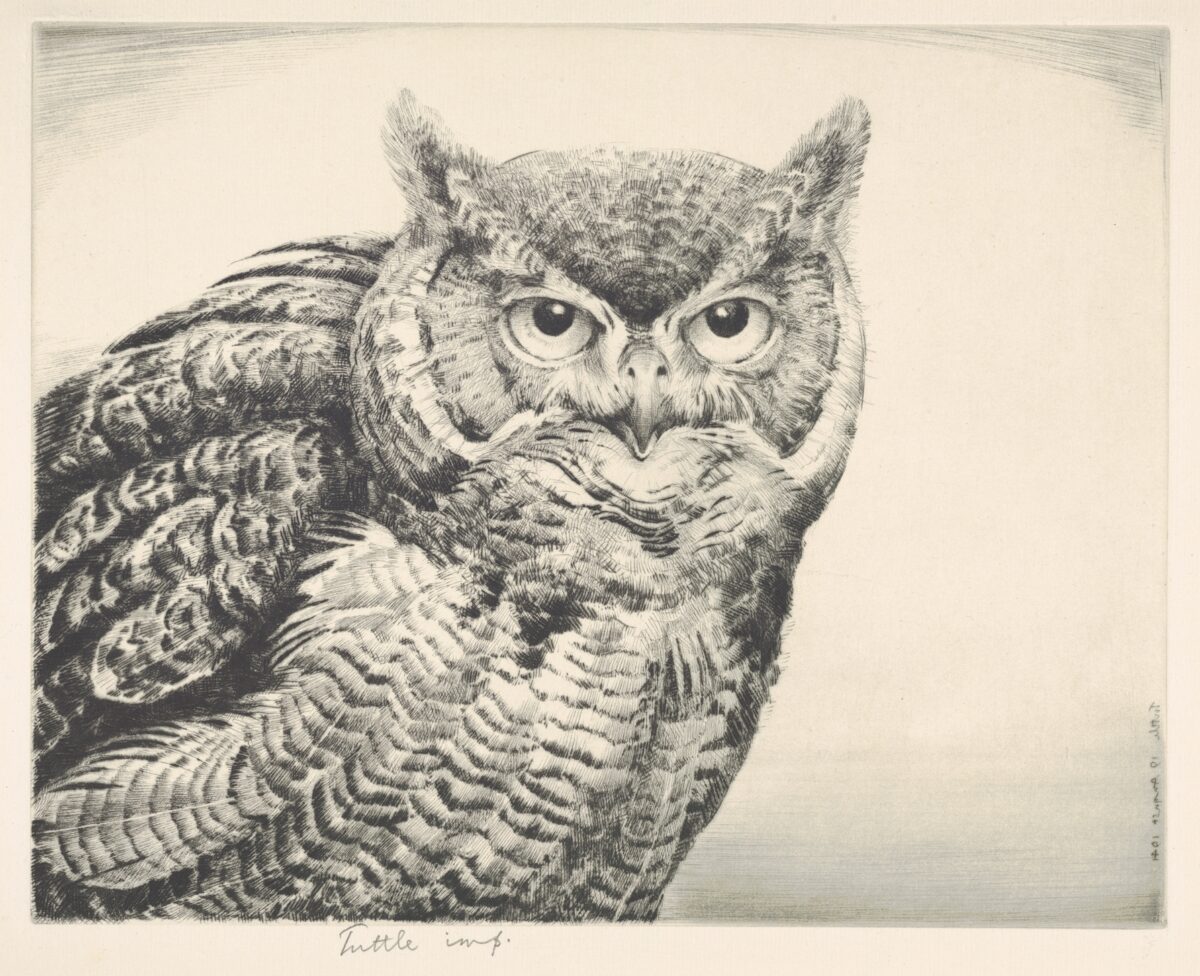

Illustration for “The Fox and the Crow” from Aesop’s Fables. Photo: Flickr.

The Teachings of the Fox

The fox is universally associated with wit, adaptability, and subversion. It reminds us that cunning, observation, and strategy can overcome the strongest opponent. The fox destabilizes and unsettles, but in doing so, it reveals new paths. In stories, its tricks are not purely destructive but transformational, forcing humans to question appearances and adapt creatively.

And as the Romanian Song of the Dawn reminds us, this wisdom extends even to the threshold of the Otherworld. On that note, remember the fox’s words from Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

www.NettlesGarden.com – The Old Craft

Janese Freeman | October 11, 2020

|

I recently moved into a new home,and was given a stainglassed fox light,the person that gifted

This item to me is not a good person and might have ill intent towards me.

What should I do with it?

Alexander H. | October 12, 2020

|

Just clean it with a ritual you know for such purposes.

Maybe redirect the intention of the giver back to him or her. If you feel uncomfortable having it in your home donate it, after the cleansing.