It appears that people have first worshipped the dead. Archaeological evidence shows that people have practiced funerary rituals for hundreds of thousands of years. During the Upper Paleolithic period, early modern humans often buried their dead with tools, ornaments, or other ritual items. They sometimes placed bodies in a fetal position, perhaps reflecting a belief in rebirth or a return to the womb. Even earlier, archaic humans showed signs of deliberate care for the dead, suggesting that humans have long had emotional and ritual responses to death.

Early forms of mourning and ritual may have laid the groundwork for the belief in the soul, the afterlife, and the spiritual significance of death. In other words, our emotional capacity for grief and care has been a key driver in the development of religious thought and ceremonial practices.

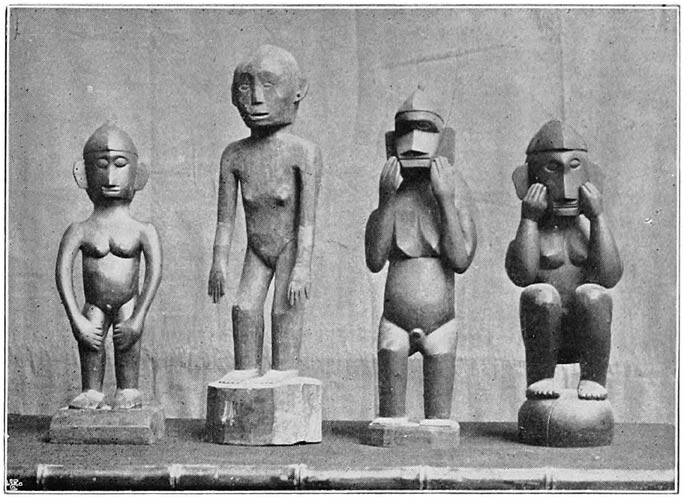

Anitos of Northern tribes (c. 1900, Philippines)

Dead Veneration Traditions

Across the world, diverse cultures practice traditions of ancestral veneration, remembering and honoring those who have passed away. Many cultures believe that ancestors continue to exist in some form and can help or guide the living.

In Africa, ancestors are often seen as messengers between humans and gods. People make offerings, sacrifices, or perform rituals to honor them. For example, the Serer people of Senegal venerate ancestral spirits called pangool. The Malagasy peoples of Madagascar also perform a ritual called famadihana, which involves exhuming and rewrapping the remains of ancestors in fresh cloth and celebrating their memory.

In Asia, many cultures believe that the dead can influence the living. In China, families burn incense and offer food or joss paper to honor ancestors. In India, the śrāddha rituals are performed to ensure the peace and happiness of ancestors. In Japan and Korea, people keep household altars and hold annual ceremonies, such as Obon and charye, to honor the dead. In Southeast Asia, ancestors are honored through festivals, offerings, and spirit ceremonies, such as the anito in the Philippines and Faun Phii in Thailand.

In ancient Europe, people set aside special times of the year to honor their ancestors. In Greece and Rome, families poured wine or food onto the ground as offerings, and festivals like the Genesia or Parentalia were devoted to remembering the dead. Romans also kept household shrines for their ancestors, while the Greeks maintained a cult for their heroes.

For Celtic peoples, the autumn festival of Samhain in Ireland and Scotland, or Calan Gaeaf in Wales, marks a liminal time when the living welcome the spirits back with food, drinks, and bonfires. In northern Europe, Germanic and Norse communities celebrated Yule, when offerings to ancestors were made for protection and fertility.

Across the Americas, European settlers brought influences from Samhain and solstice festivals, while Indigenous cultures practiced ancestor veneration by building altars, making offerings, and performing dancing ceremonies. In Mexico, Día de los Muertos continues pre-Columbian practices blended with Catholic customs, with families creating ofrendas of food, flowers, candles, and personal items to welcome returning spirits.

Christianity later reshaped some of these older practices into All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2). Even today, families across Europe visit cemeteries, light candles, and give prayers or alms for their dead, especially during winter (around Christmas) and in spring (around Easter). Despite changes over time and cultural differences, the core practices remain the same: offering sustenance, remembrance, and continuity not only for the dead but for ancestral traditions.

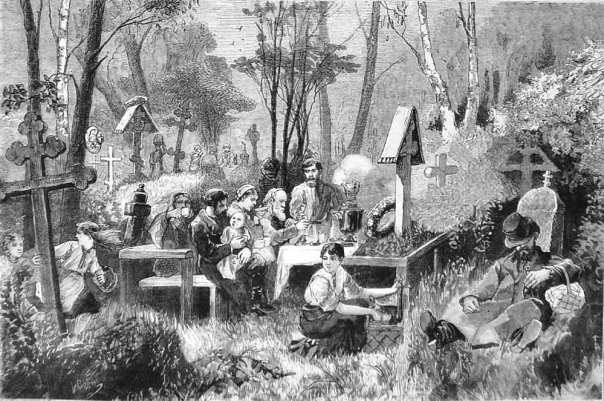

Easter of the Dead and Radonitsa are ancestor feasts where families gather in cemeteries to honor and reconnect with their departed.

Dead Veneration in Romanian Tradition

The Romanian cult of the dead and ancestors is a rich example of pre-Christian and Christian syncretism. The attention given to the dead is motivated by both reverence and fear of the consequences of neglecting ritual. The deceased are believed to return as strigoi if their rites are ignored, and such is seen not only as a misfortune upon the family but also the entire community. The strigoi are said to bring disease, drought, or deluge if they are not properly put to rest.

Funerary rites are thus highly structured, involving careful preparation of the body, ritual objects such as coffins, crosses, or funeral trees, and the performance of ritual songs and prayers for the departed based on their lives. For example, those who passed away before marrying would receive distinctive rites, such as being assigned a posthumous spouse in the form of a fir tree.

In some regions, people also performed second burials, similar to the Malagasy famadihana. Several years after death (five for a young woman, three for a child, and seven for an elderly person), bones were exhumed, washed with water and wine, wrapped in cloth, and carried to the church for a memorial service, then returned to the cemetery for reburial.

As noted in the Encyclopedia of Death and Human Experience, second burials can be found in Asia (e.g., Kalimantan, China, Japan, Taiwan), Africa (e.g., Mali and Madagascar), Australia, and in Europe (e.g., Greece, France, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands), and they conclude the cycle of mortuary rites, allowing the deceased’s journey to the Otherworld to be completed.

The journey of the soul of the dead to the Otherworld is guided by the Romanian Book of the Dead. Similar in purpose to the Egyptian and Tibetan Books of the Dead, the Romanian variant is an oral compendium of ritual texts, songs, and instructions performed by female choirs at specific moments during the preparation of the body, along the path to the cemetery, and during burial to guide the deceased, invoke protective spirits, and ensure the soul can navigate obstacles.

The dead are commemorated periodically after burial for several years, after which they enter the cult of ancestors. The Romanian folk calendar observes multiple communal Ancestor Feasts throughout the year, which mark both pre-Christian seasonal cycles and Christian liturgical observances.

For example, between Christmas and Epiphany, families perform divination to seek guidance from ancestors, set tables for the dead, offer food, drink, bread, and candles, and purify graves with holy water and incense.

On the Easter of the Dead, celebrated a week after the Orthodox Easter, families give alms such as bread, cakes, wine, cooked dishes, and symbolic items for the souls of the dead. Some rural communities also shared meals in cemeteries and performed traditional funerary dances at the graves.

At Whitsun, the spirits of the dead lingering in the world of the living were believed to become restless or aggressive. Families appeased them by distributing decorated vessels filled with food, bread, drinks, and alms to neighbors or leaving them at graves. Protective practices, including anointing windows with garlic or lovage, were also performed to ensure the spirits returned to the Otherworld.

These practices do more than help the dead. They bring communities together. When people participate in rituals, follow the folk calendar, and share offerings, they strengthen social bonds and pass down cultural memory.

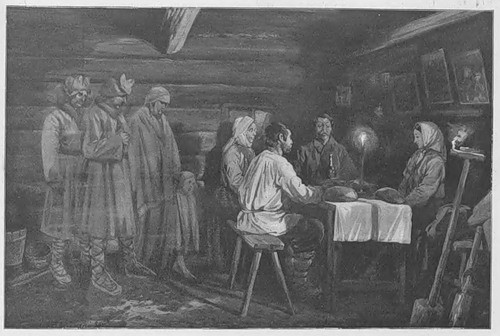

Sacrificial supper. “Forefathers, great-grandfathers, come to us!”, painting by Stanisław Bagieński

The Mythical Ancestors

Over time, the dead become part of cultural memory, eventually taking their place among the ancestors. They are no longer remembered only as specific individuals but as collective figures from a sacred source or “Time of Origin” to which they have returned, and from which they reveal transcendent values that guide human life. As Mircea Eliade noted in The Myth of the Eternal Return:

“The transformation of the dead person into an ancestor corresponds to the fusion of the individual into an archetypal category. In numerous traditions (in Greece, for example) the souls of the common dead no longer possess a memory; that is, they lose what may be called their historical individuality. The transformation of the dead into ghosts, and so on, in a certain sense signifies their reidentification with the impersonal archetype of the ancestor. The fact that in the Greek tradition only heroes preserve their personality (i.e., their memory) after death is easy to understand: having, in his life on earth, performed no actions which were not exemplary, the hero retains the memory of them, since, from a certain point of view, these acts were impersonal.”

Therefore, in the cult of ancestors, the dead become symbolic guides, protective spirits, or sources of moral authority, representing the collective memory of the lineage or community rather than the personal story of an individual. Meanwhile, heroes preserve their memory and personality after death because of their extraordinary lives. They are celebrated in stories, cults, and rituals not just as ancestors but as figures whose deeds continue to inspire and guide the living.

www.Nettlesgarden.com – The Old Craft

Selene | November 2, 2018

|

Hello,

I discovered your site by researching ancestor worship. your article describes a really very interesting approach.

However, I realize that for people who, like me, do not know their parents of origin and cfoup or their blood ancestors the connection will prove very complicated to establish because: no names, faces, objects, personal effects,…

So although they are there, the communication is complicated because there is no anchor. the fact of not having objects or information to hang on does not guarantee secure access to the ancestors of the blow is more complicated!

Thank you for your article

Joseph | May 15, 2019

|

everything is an Essence of an Energy. call your ancestors and even if you do not know of them, trust me, they will know you

IFADOYIN | November 11, 2023

|

Truth.

Elizabeth Reynolds | August 8, 2020

|

Hello thank you for your post are there any books you would recommend for ancestral magick?

Deanna morris | February 1, 2021

|

You probably tell me more.. 3/12/71 owl/ fire/ Irish methidest/ always had sarah/ intution is excellent after i put protection blessing my own mix with psalm 91 lent shield kept sword etc mote be few arch angels Michele Ariel. figg Inanna i left out should have put in.. 10 mins after mentioning someone they turn up.. Saturn and Another war planet not sure now.. Very old book handed to me i already knew what i had old boyfriend took it scared of it i had seen both by then not a complete reigous person look for protection blessings cursed as a baby..only just told.. Can you look more for me My name is Deanna christine morris maiden name gosper, wenhams and Farley mothers side. Muxlow other side mother grandfather.. Dad gosper, smith, ???