The wolf marks the onset of winter, guiding people to stand firm in the face of adversity.

In Romanian legends, fairy tales, and folk beliefs, the wolf is a profoundly ambivalent creature. It appears sometimes as an adversary, other times as a protector and ally of heroes. Within myth and ritual, it may act as a divine messenger or a demonic agent. The wolf’s ambivalence is explained in the Romanian myth of creation, which tells that the Devil shaped the wolf from clay, but God gave it life and, in turn, charged it with pursuing the Devil. Thus, the wolf is perceived as both a creature of darkness and a servant of divine will.

A Symbol of Thresholds

The wolf holds a powerful presence in charms, initiation rites, and seasonal rituals, otherwise important thresholds for rural communities. In the Romanian folk calendar, it heralds the coming of winter. Toward the end of November, rural communities observe Ovidenia and the Night of the Wolf (Saint Andrew’s Day), which mark the onset of winter and the wolf’s mating season. During this liminal time, the wolf’s mystical powers are believed to reach their height, granting it the ability to see and banish evil spirits. Its very name is treated as taboo during the celebrations, and it is believed that, if spoken aloud, it could summon wolves to the village.

In certain regions, newborns were ritually introduced to life through a device called the “wolf’s mouth”, made from a wolf’s jawbone and hide. Recorded in Hunedoara, this practice symbolically imparted the wolf’s strength and resilience to protect the child from illness. Some children would also be renamed after the wolf. Derivative names from “lup”, such as Lupu, Lupan, Lupușor, Lupașcu, and others, were believed to draw from the creature’s vitality and scare away evil spirits.

The wolf accompanies man even in death. It is believed to be one of the psychopomp animals that guide souls to the Otherworld, as depicted in the funerary Song of the Dawn:

“And the Wolf will come before you,

To frighten you,

But do not be afraid,

For the wolf knows well

The secrets of the forests

And of the paths,

And he will lead you

To the son of a king,

To guide you into Heaven,

For there is your dwelling.”

Wolfskin Initiations: Between Magic and Martial Rite

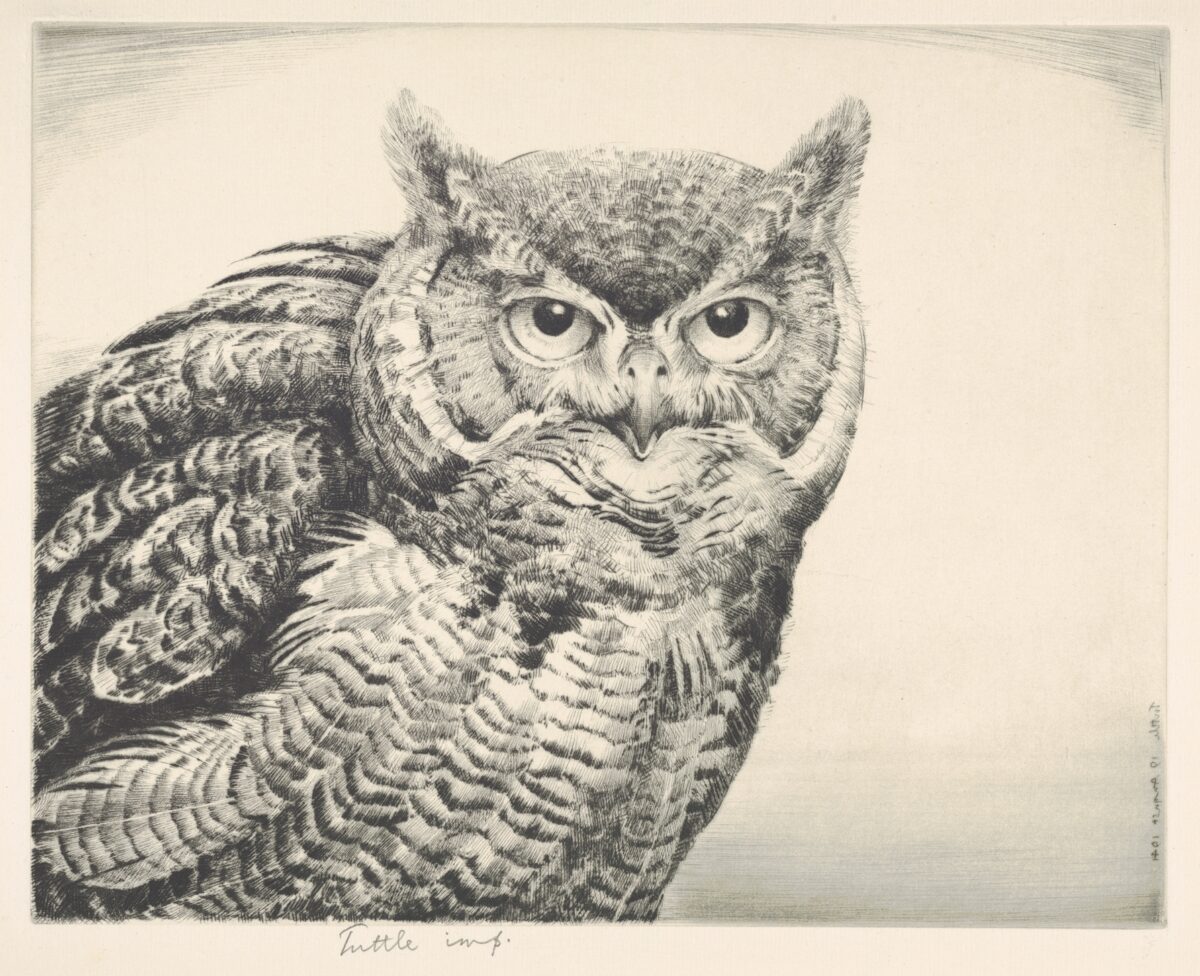

Engraving of a Vendel era bronze plate (Öland, Sweden) – depicting a berserker following Oden.

The transformation of humans into wolves is a widely attested theme. In Romanian folklore, werewolves called pricolici are often the result of sacrilege or a curse. They are believed to hunt witches and evil spirits, while some are believed to be witches themselves who take the animal form to wreak havoc. Such beliefs about lycanthropy reflect shamanic and martial initiations, where humans temporarily assumed the essence of the carnivore to gain supernatural power, protection, or spiritual authority.

To defend cattle from werewolves, especially on days consecrated to the wolf, people performed a ritual of “binding the wolf’s mouth” by sealing the hearth’s opening with clay while burning embers smoldered within. Likewise, sharp objects were tied together on a string to bind the wolf’s teeth.

In folk magic, parts of the wolf were regarded as potent apotropaic objects for warding off misfortune and channeling supernatural forces. Wolf hair was burnt to fumigate the sick and heal fright, while fangs were carried as charms for good luck. Consuming wolf liver was thought to cure tuberculosis, and other parts were used in spells or to summon the devil. Sorcerers were said to call spirits through a wolf’s snout, as though through a funnel. Wolf masks and effigies were also used by carolers in winter festivals to banish evil forces. In some villages, it was believed that if the masked carolers danced for barren women, it would help them become fertile.

Totem of Warriors and Ancestors

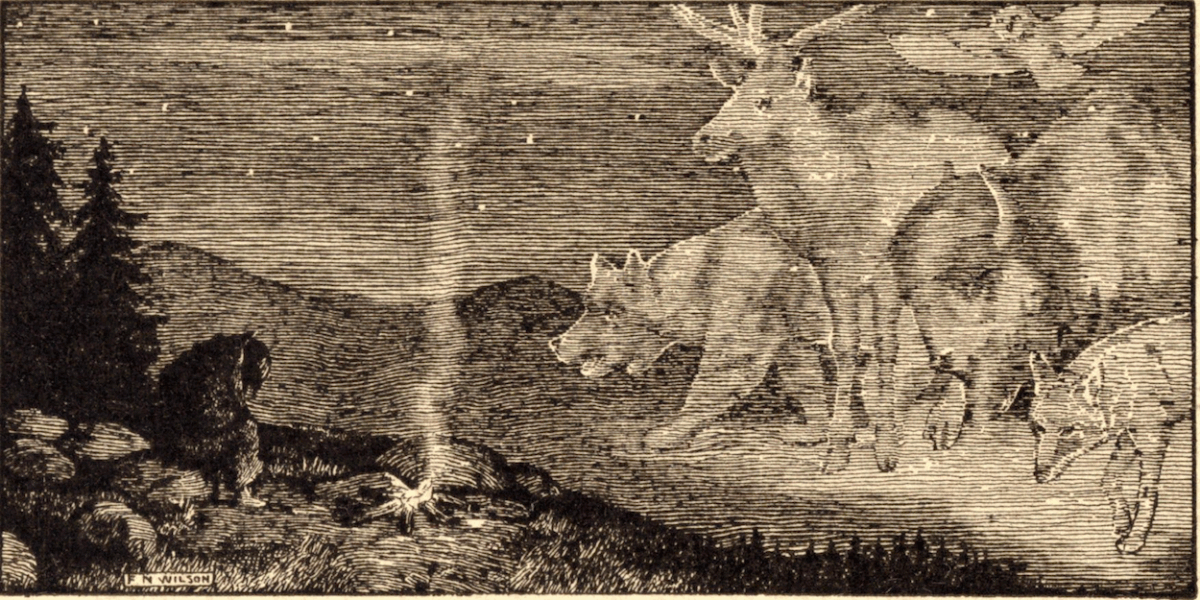

Capitoline Wolf Statue, Cluj-Napoca, Romania – depicting the mythical she-wolf Lupa with Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome.

The prominence of wolf folklore in the Balkano-Carpathian region stems from a broader Indo-European religious and martial framework in which the wolf was revered as a sacred totem and mythical ancestor. Tribal names derived from animals carried religious significance across the ancient world, and wolf names, especially, were common among Indo-European peoples. The Dacian ancestors of the Romanians called themselves daoi (“wolves” or “wolf-like”), according to Strabo. Notably, certain nomadic Scythians east of the Caspian were also known by this name.

Historian of Religions Mircea Eliade argued that such names originated either from a divine or mythical ancestor manifesting in wolf form, such as in Central Asian myths of tribes descended from a she-wolf, or from marginal groups of exiles, immigrants, or young warriors surviving through raiding, or from the ritual of transformation into wolves.

The wolf as a symbol of exile can be found throughout Indo-European myth. Deities of outcasts often bore wolf attributes, such as Zeus Lykoreios and Apollo Lykeios. And Rome’s founders, Romulus and Remus, who were nursed by the she-wolf of the Capitol, were fugitives themselves.

As for the ritual of transformation into wolves, martial initiations among some Indo-Europeans involved the imitation of the wolf’s ferocity and behavior, and surviving on the fringes in “wild packs.” For example, Germanic warriors like the berserkir (“in bear-skin”) and the ulfheðnar (“in wolf-skin”) were known to assume this animal identity.

For the Dacians, the wolf was a military totem, as depicted by their Draco standard, a dragon with a wolf’s head, symbolizing the power, ferocity, and agility of wolves in battle. This symbol also appeared in Central Asian, Iranian, and other Indo-European cultures, including Germanic tribes who had wolf or dragon symbolism on their standards.

The Wolf Across Cultures

The wolf’s mythic roles in Romanian folklore resonate with a wider, near-universal symbolism. Across cultures, the wolf is a paradox of danger and protection, exile and belonging, terror and initiation.

In ancient Greece, the wolf walked alongside the gods Apollo Lykeios and Zeus Lykoreios. In Norse mythology, Fenrir, the devourer of worlds, symbolizes the apocalypse itself, while Odin’s own wolves, Geri and Freki, mark his power and paradox. Across the Americas, the wolf is a pathfinder, a symbol of kinship, and a companion to the first human. Among Turkic and Mongolic peoples, it is a mythical ancestor and sacred spirit. Everywhere, the wolf seems to thread through human imagination as an untamed spirit.

The persistence of these images suggests that the wolf reflects humanity’s own ambivalence. Like humans, wolves are social predators, bound by loyalty to the pack yet feared for their violence. They are outsiders and kin, simultaneously embodying chaos and sacred power.

www.Nettlesgarden.com – The Old Craft

Michiel | May 4, 2018

|

Thank you yet again for an amazing and very informative article!

Radiana Piț | May 4, 2018

|

You are most welcome! Thank you for your positive feedback 🙂

Erik | September 13, 2018

|

thank you, i did something to try to visualize what spirit animals i had, but some of them i never thought i have and i dont know there meaning… i dont know if you could help me with this…. what i seen where many… and some shockly traits one of them have.. if u are willing to hear me out, i dont mind telling u what i seen..

Shadeed R. Ahmad | September 23, 2018

|

This is the most informative, interesting and inspiring article I’ve ever read on the wolf. Truly your heart and soul were put into this wonderful writing. Thank you for sharing these spiritual insights. Please keep up the beautiful style and content you display… Sincerely, Shadeed A.

Anindo Choudhury | March 17, 2020

|

Can I call call wolf sprit, if someone owes money to me and delaying the process of returning the money to me,can wolf help me