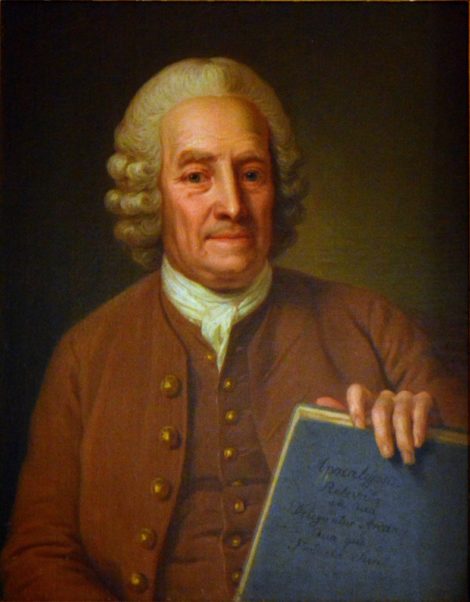

Portrait of Emanuel Swedenborg by Carl Frederik von Breda (c. 1818). Swedenborg was considered mad, but brilliant by many, especially for his view that God is Divine Goodness who is neither vindictive nor in need of Christ’s atonement for Adam’s sin.

On July 19, 1759, a devastating fire broke out in Stockholm, Sweden. It spread rapidly, destroying nearly 300 homes in its path. About 400 km away from Stockholm, in Gothenburg, Swedenborg was having dinner with his friends. At about 6 o’clock, he became visibly anxious and confessed to his friends that a fire had broken out in Stockholm and threatened to burn down his home.

At 8 o’clock, he was relieved, saying that the fire had stopped just three doors away from his house. Word of Swedenborg’s strange claims reached the provincial governor, who that same night summoned him to recount his story in detail. Three days later, couriers from Stockholm reached Gothenburg with news of the fire, validating Swedenborg’s story down to the precise hours when the fire had started and when it had stopped.

Emanuel Swedenborg, one of the most complex historical figures of the 18th century, was also a mystic who claimed to experience visions and strange dreams frequently.

While he is primarily known for his philosophy and theology, Swedenborg was a polymath whose areas of study and expertise included mathematics, geology, metallurgy, mineralogy, crystallography, anatomy, chemistry, physics, cosmology, and more. His life and spiritual views laid the foundations of Swedenborgianism and the New Church, and exerted a lasting influence on later movements such as Spiritualism and Theosophy

Swedenborg’s place of birth is commemorated at Hornsgatan 43, in Stockholm, Sweden. Photo: Creative Commons.

Swedenborg’s Life and Spiritual Awakening

Emanuel Swedenborg (Swedberg) was born on January 29, 1688, in Stockholm, Sweden, as the son of Jesper Swedborg, the bishop of Skara. He is one of the most notable churchmen in Swedish history, having received a noble honor from Queen Ulrika Eleonora after King Charles XII’s death, which changed the family name from Swedborg to Swedenborg. Jesper is famous for his criticism of the Lutheran Church in Sweden and his beliefs that he passed down to his son. More notably, Jesper’s belief in angels and spirits greatly influenced Emanuel’s own beliefs.

After graduating from Uppsala University in 1709, Emanuel Swedenborg traveled through the Netherlands, France, and Germany, finally making his way to London, England. He lived there for four years. Because London was a central location for science at the time, he developed an interest in physics and mechanics, alongside his interest in philosophy and poetry.

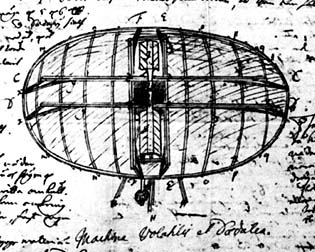

Sketch of Swedenborg’s Flying Machine. He first sketched it when he was 26 years old and later published it in his Daedalus Hyperboreus in 1716.

Over the course of two years, Swedenborg developed engineering projects, like the “Lost Draft Invention of a Submersible Ship” and the “Flying Machine,” which he started sketching a few years earlier.

Because of his reputation as a scientist, he was offered a chair of mathematics at the University of Uppsala in 1724, which he refused, saying that his main interests were geometry, chemistry, and metallurgy, and that because of his stutter, he did not have “the gift of eloquent speech” worthy of a professor or public speaker. However, what he did not speak, he wrote. According to Swedish critic Olof Lagerkrantz, Swedenborg’s extensive argumentation in writing was due to his speech impediment.

In the 1730s, Swedenborg turned to anatomy and physiology, advancing ideas that strikingly anticipated later scientific discoveries, even if often in speculative form. It was around this time that he also began to study the relationship between spirit and matter, developing his own philosophical method, and the idea that the soul may be based on material substances (De Infinito).

In 1743, Swedenborg planned a journey abroad to collect material for his Regnum Animale, an ambitious work intended to explain the anatomy of the soul in no fewer than seventeen volumes. During his stay in the Netherlands in 1744, he began experiencing a series of vivid dreams, which he recorded in his Journal of Dreams. Discovered in the Royal Library in the 1850s, this diary documents six months of increasingly distinctive visions Swedenborg claimed to have. The final entry, dated 26–27 October 1744, records his realization that he must abandon the Regnum Animale and devote himself to a new path. Shortly thereafter, he began another project, De cultu et amore Dei, which, though left incomplete, was nevertheless published in 1745.

The same year, Swedenborg claimed to have experienced a spiritual awakening. He claimed that the spiritual world had first opened to him on the Easter Weekend of 1744, when God enabled him to visit heaven and hell at will, and chose him to write the Heavenly Doctrine, which would reform Christianity.

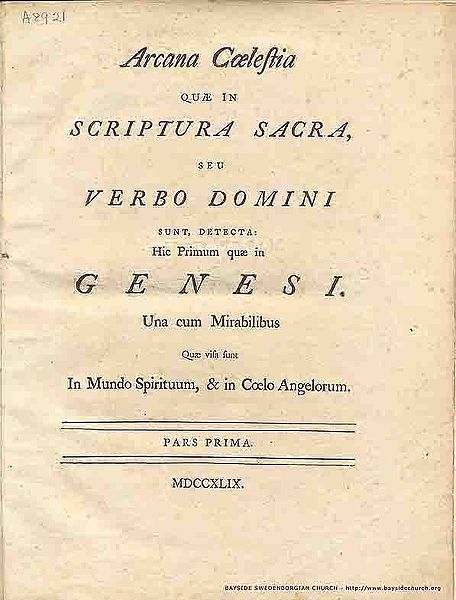

Title page from the first edition of Arcana Coelestia, 1749. Swedenborg’s interpretation gave spiritual meaning to those who couldn’t understand the Scriptures.

Swedenborg spent the last 28 years of his life investigating spiritual matters. In June of 1747, he resigned from his professional duties to fully dedicate himself to completing a new project. He began studying Hebrew and intended to make a spiritual interpretation of every verse of the Bible. For 10 years, he worked on The Arcana Cœlestia, widely regarded as his magnum opus. It comprises eight volumes, published anonymously from 1749 to 1756, and Swedenborg was formally identified as its author in the late 1750s

Arcana Cœlestia interprets the spiritual significance underlying the biblical books of Genesis and Exodus, while still affirming the historical reality of the events they recount. Swedenborg interprets these narratives as symbolic representations of deeper spiritual truths. As he explains in the opening paragraph of the first volume:

“From the mere letter of the Word of the Old Testament no one would ever discern the fact that this part of the Word contains deep secrets of heaven, and that everything within it both in general and in particular bears reference to the Lord, to His heaven, to the church, to religious belief, and to all things connected therewith; for from the letter or sense of the letter all that anyone can see is that ̶ to speak generally ̶ everything therein has reference merely to the external rites and ordinances of the Jewish Church. Yet the truth is that everywhere in that Word there are internal things which never appear at all in the external things except a very few which the Lord revealed and explained to the Apostles; such as that the sacrifices signify the Lord; that the land of Canaan and Jerusalem signify heaven ̶ on which account they are called the Heavenly Canaan and Jerusalem ̶ and that Paradise has a similar signification.”

The headquarters of the Swedenborg Society, founded in 1810. The society has resided there since 1925. Creative commons.

After completing Arcana Cœlestia, Swedenborg continued to write theological works. In 1758, he published The Last Judgment, in which he claimed to have witnessed the event occurring between 1757 and 1758 in the spiritual realm. He described this judgment as taking place “halfway between heaven and hell” in the World of Spirits. He believed the judgment was necessary because the Christian Church had become faithless and corrupted, and thus disturbed the balance.

Swedenborg’s most popular work to this day is Heaven and Hell, published in 1758. In it, he recounts his visions of the afterlife, portraying death as a peaceful transition into a spiritual realm where spirits are received by angels. He describes this realm as more real than the physical world. Heaven, in his vision, is a “geography of love,” where individuals are situated according to their deepest loves and are able to realize their best selves. The work also contains elaborate depictions of angels and divine worship.

Swedenborg completed his final work, Vera Christiana Religio, in July 1770. Just before Christmas 1771, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and bedridden. In February 1772, Swedenborg corresponded with John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. Wesley mentioned that he was about to embark on a six-month journey and would contact Swedenborg upon his return. Swedenborg replied that it would be too late, as he was soon to die. He passed away on 29 March 1772 in London. According to reports from his servant, Elizabeth Reynolds, he had anticipated the timing of his death and spoke of it with peace and acceptance.

Emanuel Swedenborg’s Tomb in the Uppsala Cathedral, Sweden. Foto: Francisco Anzola, CC.

According to his friend and landlord, Pastor Arvid Ferelius of the Swedish Church in London, when he asked Swedenborg if he would like to recant anything in his final hours before death, Swedenborg raised himself up, put a hand on his heart and said: »As truly as you see me before your eyes, so true is everything that I have written; and I could have said more had it been permitted. When you enter eternity you will see everything, and then you and I shall have much to talk about«.

Swedenborg And Swedenborgism As Influence on the Occult

Swedenborg’s teachings were popular with enthusiasts of the 19th-century Occult Revival. For them, Swedenborg was a visionary whose doctrine of correspondences was aligned with the theosophical tradition of alchemist Paracelsus or the mystic Jakob Böhme, and who, like John Dee, communed with angels. On the other hand, Kant criticized Swedenborg’s visions as mere “dreams of a spirit-seer.”

Despite sympathy from Western esotericists, Swedenborg never held himself out as one. Rather, the interest in the supernatural trending at the time made Swedenborgism an attractive philosophy.

Emanuel Swedenborg with a print of “Apocalypsis Revelata” (The Apocalypse Revealed). Painting by Per Krafft the Elder, 1766.

Alchemist and hermetician Dom Pernety (1716-1801) was a colleague of Swedenborg and translator of his Latin work into French. The Berlin circle around Pernety had personal contacts with Swedenborg. The French Martinist and leading member of Pernety’s hermetique rite and Illumines d’Avignon, Benedict Chastanier, was one of the first Swedenborgians to spread his “gospel” into England’s masonry.

The Swedenborgian Rite, sometimes attributed to a Marquis de Thorn, sometimes to a Marquise de Thome, consisted of six degrees (Apprentice, Fellow Craft, Master Neophyte, Illuminated Theosophite, Blue Brother, and Red Brother) and was built on top of the hermetique rite as practiced in circles around the Illumines d’Avignon. While the Masonic Swedenborgian Rite was short-lived in England at first, it made its way into American Masonry and found its way back to England at the end of the 19th century.

While Swedenborg’s ideas have influenced Masonic traditions, there is no concrete evidence that he was a Freemason himself or directly engaged with Masonic organizations. The connections between Swedenborg and Freemasonry remain indirect and are primarily based on the adoption of his teachings by Masonic groups.

Swedenborg never founded a church, a cult, or an order. Yet, his teachings and theology influenced many who, after his passing, gathered in small study groups to read and discuss his work. His Heavenly Doctrine appealed to those who felt that Christianity at the time had to be reformed. Swedenborg’s reputation as a seer, his accounts of talking to angels, and his belief in a heaven of divine love for all became the fundamental beliefs of the New Church of Jerusalem, founded on May 7, 1787, in England.

The New Church believes that Swedenborg was chosen by God to write down his Heavenly Doctrine. Their fundamental Swedenborgian belief is that God, infinite and loving, is at the center of life, that the Bible contains deeper spiritual meaning for the soul, that those who pass become angels or spirits, and that heaven is dictated by state of being and what one loves most.

One of Swedenborg’s earliest readers was poet and artist William Blake, whose own visions of the spiritual world have intrigued many. While he was attracted to Swedenborg’s vision of divine love, he was repelled by the doctrine of the New Church. His satire The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, was deeply influenced by his rejection of Swedenborgism.

Ornament from “Arcana Coelestia” depicting two angels close to the Sun. Swedenborg claimed that “Angels never attack, as infernal spirits do. Angels only ward off and defend.”

During the Occult Revival, when followers of Swedenborgism blended the mystical aspects of Swedenborg’s work with divination, spiritism, alchemy, and theosophy, Heaven and Hell became a favorite among those in the Spiritualist movement who were particularly interested in the afterlife. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote in the first volume of The History of Spiritualism: “In point of fact, every Spiritualist should honor Swedenborg, and his bust should be in every Spiritualist temple, as being the first and greatest of modern mediums.”

The association with Spiritualism was opposed by some Swedenborgian groups, stating that the practice of spiritualism may be dangerous and against Swedenborg’s recommendations, while others sided with the Spiritualist movement and embraced the practice. While Swedenborg himself was open and candid about his visions and alleged experiences, he cautioned against contacting the spirit world, as it might invite unwanted spirits.

He believed that the ability to communicate with the spirit world must come from God, rather than being a skill that should be developed. However, Swedenborgian spiritists dismiss these warnings and continue to credit Swedenborg as one of the first modern mediums.

Eliphas Levi commented on this in The History of Magic: “The means proposed indirectly by Swedenborg for communication with the supernatural world constitute an intermediate state allied to dream, ecstasy and catalepsy. The illuminated Swede affirmed the possibility of such a state, without furnishing any intimation as to the practices necessary for its attainment.”

Because of Swedenborg’s growing popularity with spiritists, his teachings appealed to the Theosophical Society. Helena Blavatsky cited him in Isis Unveiled:

“It is a belief (founded on knowledge) among the kabalists, that no more than the Hermetic rolls are the genuine sacred books of the seventy-two elders – books which contained the ‘Ancient Word’ – lost, but that they have all been preserved from the remotest times among secret communities. Emanuel Swedenborg says as much, and his words are based, he says, on the information he had from certain spirits, who assured him that ‘they performed their worship according to this Ancient Word’. ‘Seek for it in China,’ adds the great seer, ‘peradventure you may find it in Great Tartary’!”

She revered Swedenborg and often cited him to serve herself, but she also criticized his inability to overcome his “ingrained Christian theology,” which, according to her, limited his vision. She also claimed that Swedenborg couldn’t tell the difference between his spiritual visions and his vivid imagination because he was an untrained medium. In the Theosophical Glossary, she wrote:

“His clairvoyant powers, however, were very remarkable; but they did not go beyond this plane of matter; all that he says of subjective worlds and spiritual beings is evidently far more the outcome of his exuberant fancy, than of his spiritual insight. He left behind him numerous works, which are sadly misinterpreted by his followers.”

Blavatsky was not the first nor the last to suggest that Swedenborg might’ve had a vivid imagination. Many believe that he must’ve suffered from a mental illness, but not everyone agrees. Specialists argue that Swedenborg’s experiences should be understood as “hallucinations without mental disorder.”

Although Swedenborg’s writings fueled the hopes, dreams, and ambitions of 19th-century Western esotericists, he himself comes across as sincere. His detailed accounts of spiritual experiences and visions are presented with a straightforwardness that suggests he truly believed in what he was reporting. Unlike many later interpreters who might have used his ideas to support their ambitions, Swedenborg’s work reads as a sincere effort to convey his understanding of the spiritual world, grounded in personal conviction rather than the desire for influence or notoriety.

www.Nettlesgarden.com – The Old Craft