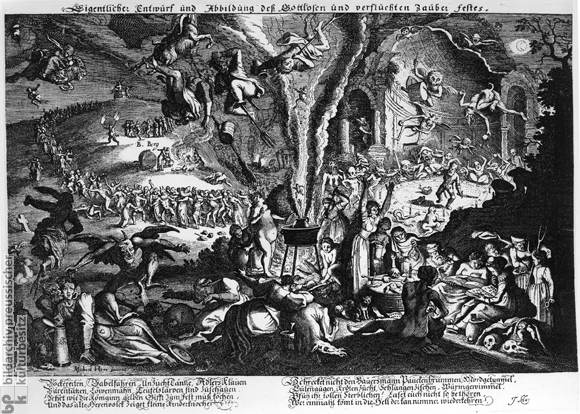

“Witches near Treves” (1600). Many of the depictions of the witches’ flight to the Sabbath were inspired by the confessions of accused witches, who shared their visions and sensations of flight with the accusers.

It is said that on April 30th, for Walpurgisnacht, witches, warlocks, and wizards gather for the Great Sabbath of the year. Some fly to the meeting places on their brooms or forks, others transform into cats, goats, horses, and toads for the journey, or they may even leave their bodies and attend the gathering in spirit. In their place, only a vicarium daemonem remains, their demonic double.

They gather just before midnight at crossroads, mountain tops, and in forests, they light a roaring bonfire which they jump through and dance around, until their Horned God arrives in their midst and the true Night of the Witches begins. This vision of the Witches’ Sabbath is but a Christian reconfiguration of ancient Dionysian mysteries.

“Saint Walburga” at St. Martin’s Church in Messkirch, by Master of Messkirch (1500s). She is celebrated on Walpurgisnacht by Christians as a protector against witchcraft.

Walpurgisnacht is an important sabat of the year, it is a night of “bewitched bodies” that “glow with flames through and through”, of “werewolves and dragon women passing by in flight” (Die erste Walpurgisnacht), when witches fly on their brooms to mountain tops where they conjure the ancient magic of the old gods.

Walpurgisnacht or Hexennacht, which is celebrated in the Germanic countries of central Europe, is similar to Beltane (May 1) or the Romanian Saint George (April 23). And because it is believed to be a magically potent and thus dangerous night, the Christian Church has appointed a patron saint and protector.

Saint Walpurga

For Christians, Walpurgisnacht is the Feast of Saint Walpurga, which is celebrated from the evening of April 30 to May 1st. Saint Walpurga or Walburga was the daughter of St. Richard the Saxon Pilgrim and sister of St. Willibald and St. Winibald. When her father went on a pilgrimage with her two brothers to the Holy Land, he left Walpurga, who was only 11 years old at the time, with the nuns of Wimborne Abbey, where she was educated and learnt how to write.

She traveled to bring German pagans to the Christian faith, and she authored Winibald’s biography, which is why she is considered one of the first female authors in Germany and England. Walpurga became a nun in Heidenheim am Hahnenkamm, the monastery founded by her brother Willibald, where she became abbess after his death in 751. Walpurga herself passed away on February 25, in 777 or 779, and she was canonized by Pope Adrian II on May 1st, around 870, when her relics were transferred to Eichstätt, Germany.

St. Walpurga is prayed to for protection against witchcraft, and it is believed that during the night of April 30, she can ward off spells, witches, and evil spirits. This belief may stem from the conflation of her canonization with Hexennacht, a Germanic tradition more prevalent in the 17th century, when witches and sorcerers were said to gather to celebrate the arrival of spring on Mount Brocken.

To protect against their magic, the Western Christian Church appointed the night of April 30 to St. Walpurga’s Feast. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Walpurgisnacht was popularized and its witchy connotations were revived through the literature of the time, such as in Jacob Grimm’s work, who wrote in 1833: “There is a mountain very high and bare… whereon it is given out that witches hold their dance on Walpurgis night.”

Goethe also dedicated a poem to the celebration called “Die erste Walpurgisnacht” (The First Walpurgis Night), which was set to music by Felix Mendelssohn and published as his Opus 60 in 1843. The poem contrasts sharply with the Walpurgisnacht described in his main work, “Faust”. In his ballad, Goethe relates the superstitions around Walpurgis night to the usage of devil masks by pagans in order to exploit the superstitions of their Christian suppressors and to protect their identities. A short background story and a translation into English of the ballad, including the music, can be found here.

Frau Holle

Ernst Ludwig Rochholz, the Swiss historian and folklorist, looks closely at the depictions of St. Walpurga and writes in his book “Drei Gaugöttinnen: Walburg, Verena und Gertrud als deutsche Kirchenheilige” (Three goddesses: Walburg, Verena and Gertrud as German church saints) from 1870:

“Holda, the good protectress”, by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine (1882).

“Nine nights before the first of May is Walburga in flight, unceasingly chased by wild ghosts and seeking a hiding place from village to village. People leave their windows open so she can be safe behind the cross-shaped windowpane struts from her roaring enemies. For this, she lays a little gold piece on the windowsill and flees further. A farmer who saw her on her flight through the woods described her as a white lady with long flowing hair, a crown upon her head; her shoes were fiery gold, and in her hands she carried a three-cornered mirror that showed all the future, and a spindle, as does Berchta. A troop of white riders exerted themselves to capture her. So also another farmer saw her, whom she begged to hide her in a shock of grain. No sooner was she hidden than the riders rushed by overhead. The next morning, the farmer found grains of gold instead of rye in his grain stook. Therefore, the saint is portrayed with a bundle of grain.”

This tale serves Walpurga’s depictions of holding a bunch of corn in one hand and the tradition of securing the barns during her intercession. Her description is similar to that of Frau Holle, whom Jacob Grimm revered as goddess Holda or Hulda.

Frau Holda was associated with witchcraft, women’s crafts, and agriculture in German folklore, and, similar to Walpurga, the spindle was appointed to her as a symbol. The distaff, which resembles a broom, was also a symbol of Frau Holda. She was believed to ride on distaffs at night with her Hulden, the nocturnal spirits of the women who became her witches.

According to the Canon Episcopi quoted by Carlo Ginzburg in his “Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath”, the Hulden went “out through closed doors in the silence of the night, leaving their sleeping husbands behind” to go to feasts or battles in the sky. According to the Canon Episcopi, if a woman was accused of such a deed, she was required to do penance for a year.

17th-century engraving by Michael Herr, depicting the events on the Blocksberg on Walpurgisnacht, accompanied by verse from the German poet Johann Klaj, warning against belief in witchcraft.

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Grimm wrote in 1888: “The Witches’ excursion takes place on the first night in May… they ride up Blocksberg on the first of May, and in 12 days must dance the snow away; then Spring begins… Here they appear as elflike, godlike maids.” The Blocksberg is also known as the Brocken, and it is the highest peak of the Harz mountains in Northern Germany.

Various rock formations on the Blocksberg have such names as Teufelskanzel (the Devil’s Pulpit) and Hexenaltar (the Witch’s Altar). The mountain has been associated with witches since the 3rd century, and it was likely a sacred site. Legends say that witches flew on broomsticks from all over Germany to gather there and conjure magic, especially during the burning times.

Another legend says that Wotan married Freya on the Brocken in Schierke, while others tell of devils and witches dwelling there. Such stories may be connected to the Brocken Spectre phenomenon, which creates eerie optical illusions and gave rise to many superstitions, all of which inspired Goethe to write about them in “Faust.”

Superstition and Tradition Throughout Europe

Engraving by W. Jury (1829), depicting the Walpurgis Night Scene from Goethe’s Faust.

People celebrate Walpurgisnacht with loud cheering and banging pots together to scare evil spirits and witches. They light ritual bonfires, which they leap over or dance around. They throw dolls made of straw into the fire, and women also burn their old brooms.

They also protect the cattle against evil witches by hanging bells on the cows’ necks. Wearing a wild radish was also believed to protect against witches and evil spirits. Walpurgisnacht was also a potent time for divination and love spells. It is said that if one sleeps with just a single sock on, they would wake up the next day to find a hair in it, of the same color as the hair of the betrothed. A traditional divinatory love spell during the night suggests placing a linen thread next to a statue of the Virgin Mary and unraveling it at midnight while saying: “Thread, I pull thee; / Walpurga, I pray thee, / That thou show to me / What my husband’s like to be.”

Walpurgisnacht in Erfurt, Germany. Photo via source

Variants of the Walpurgisnacht celebrated in Germany can be found throughout Europe in the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Sweden, Finland, and more. In Czech Republic, the night of April 30 is known as pálení čarodějnic (burning of the witches) or Valpuržina noc, while May 1 is the Day of Love. It is celebrated by young people who gather on top of the hills around bonfires where they create effigies of witches and throw them into the fire.

The Estonian variant is called Volbriöö, and it is celebrated from the night of April 30, when people dress up as witches, into May 1, when Estonians celebrate Spring Day. In Finland, people celebrate it as Vappen, while in Sweden, it is celebrated as Valborg, which marks the arrival of Spring, and both celebrations are revered as important public events. A large part of Europe celebrates its own version of Walpurgisnacht at the end of April and beginning of May to mark the beginning of summer and pay homage to the old ways.

www.Nettlesgarden.com – The Old Craft

Mark A. O'Blazney | May 1, 2018

|

+

Angela | April 9, 2019

|

Excellent Sister ❤️??♀️