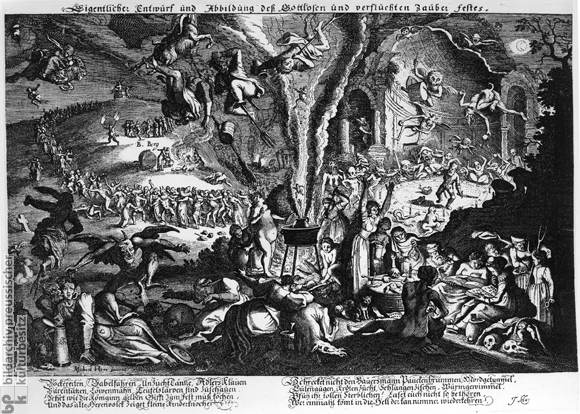

“Witches near Treves”, engraving from about 1600. Many of the depictions of the witches’ flight to the Sabbath were inspired by the confessions of accused witches, who shared their visions and sensations of flight with the accusers. These visions and sensations were often acquired after using a secret magical ointment before sleep on the night of the Sabbath

On April 30th for Walpurgisnacht, witches, warlocks, and wizards gather for the Great Sabbath of the year. Some fly to the meeting places on their brooms or forks, others turn themselves into cats, goats, horses, and toads for the journey, some leave their bodies and attend the meeting in spirit, while others cover their bodies with a secret ointment to grow bat wings so they can fly to the gathering. In their place, they leave a vicarium daemonem, their demonic double. It doesn’t matter which method is used for traveling, as long as the meeting is honored by everyone’s presence.

They gather just before midnight at crossroads, mountain tops, and in forests, they light a roaring bonfire which they jump through and dance around, until their Horned God arrives in their middle and the true Night of the Witches begins. They commune with their god and make love to him, they release their magic to defend it against the rising cross which with its shadow darkened the light of ancient magic. The Witches’ Sabbath is the conversion of ancient Dionysiac mysteries to a Christian context. The ancient fertility rites which were Dionysiac in nature were performed in the cover of the night, when the fire was brighter and when the aphrodisiacs were stronger.

The priestess performing these rites were accompanied by men disguised as mythical figures with horns and hooves, such as Faunus or Pan, and they partied for their gods, such as the drunk god, Silenus, and the horseman god, Sabazios. The priests and priestesses attending the Dionysiac celebrations covered their bodies with magical ointments which gave them vivid dreams, hallucinations, or a profound sleep. The secret recipes of these ointments survived through the Dark Ages, guarded by the witches who participated in the Great Sabbath.

Before they went to sleep on the Night of the Witches, they covered their body with these secret ointments, which gave them visions of fire, flying witches, and horned gods. In the Middle Ages, many witches testified to the sensation of flight given by some of these ointments that contained narcotics and poisonous herbs. The Inquisition tried to find out the recipes for these secret ointments, and the witches who confessed did so using code names for the ingredients they used. Ingredients like baby fat, bat blood, opium, and mandrake fed the imagination of the public that witches were evil creatures that kidnapped children to use them for their sabats.

“Saint Walburga” at St. Martin’s Church in Messkirch, by Master of Messkirch, sometime around the 1500s. She is celebrated on Walpurgisnacht by Christians as a protector against witchcraft.

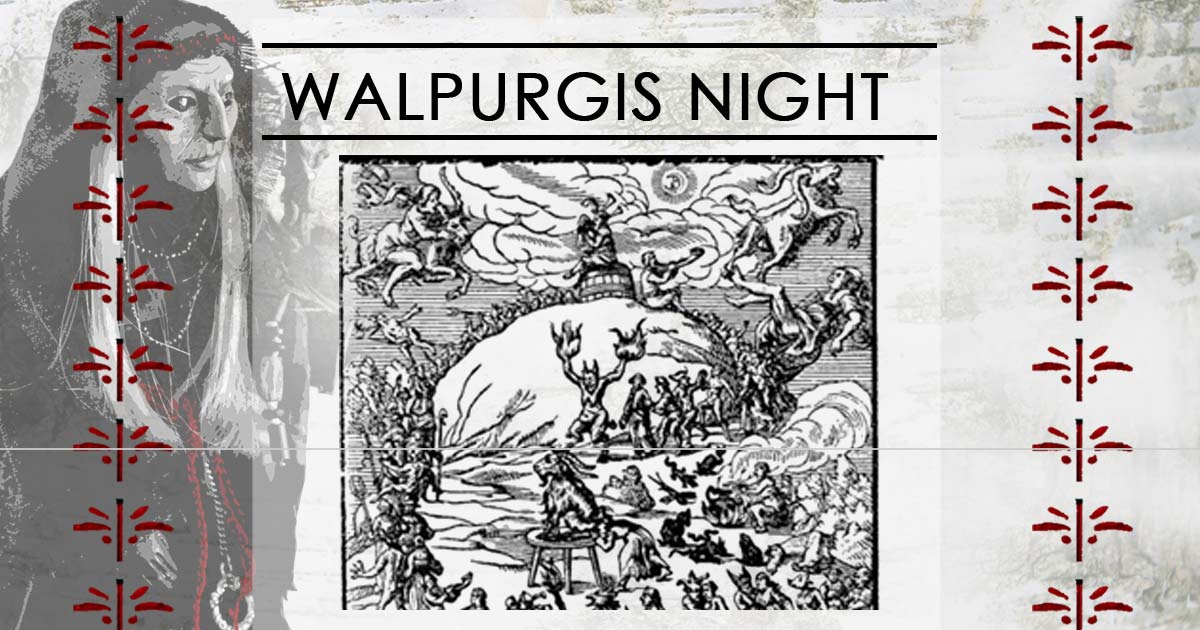

Walpurgisnacht is the greatest of all sabats throughout the year, it is a night of “bewitched bodies” that “glow with flames through and through”, of “werewolves and dragon women passing by in flight” (Die erste Walpurgisnacht), when witches fly on their brooms to mountain tops where they conjure the ancient magic of the old gods. Although the Christian Church has tried to overturn the old celebration by trying to establish a Christian patron that protects against witches on the very night of the witches, the essence of this celebration is still there and perhaps nowadays it’s embraced for what it is more than in the previous centuries.

Walpurgisnacht or Hexennacht which is celebrated in the Germanic countries of central Europe is often considered as a version of Beltane, since both fall in extremely close proximity to each other. While the celebration of the Germanic Walpurgisnacht begins on April 30th and continues to May 1st, the Gaelic Beltane is most commonly celebrated on May 1st.

A Short History of the Night of the Witches

The origins of the image of Walpurgis night being a witches’ sabbath are unclear. However, it is striking that it coincides with Beltane and maybe other pagan festivals in earlier time. Goethe presumed in one of his poems such an origin.

St. Walpurga

For Christians, Walpurgisnacht is also known as the Feast of Saint Walpurga, that is celebrated from the evening of April 30 to the day of May 1st. Saint Walpurga or Walburga was the daughter of St. Richard the Saxon Pilgrim and sister of St. Willibald and St. Winibald. When her father went on a pilgrimage with her two brothers to the Holy Land, he left Walpurga, who was only 11 years old at the time, with the nuns of Wimborne Abbey, where she was educated and learnt how to write.

She traveled in an attempt to bring German pagans to the Christian faith and she also authored Winibald’s biography, which is why she is considered as one of the first female authors in Germany and England. Walpurga became a nun in Heidenheim am Hahnenkamm, the monastery founded by her brother Willibald, where she became the abbess after his death in 751. Walpurga herself died on February 25 on 777 or 779 and she was canonized by Pope Adrian II on May 1st, around 870, when her relics were transfered to Eichstätt, Germany.

St. Walpurga is prayed to for protection against witchcraft and it is believed that during the night of April 30, she is able to ward off spells, witches, and evil spirits. This belief may stem from the overlapping of her canonization with Hexennacht or the Night of the Witches, the celebration that has its origin in ancient fertility celebrations. Hexennacht is a Germanic tradition more prevalent in the 17th century, when witches and sorcerers gathered together celebrate.

To protect against their magic, the Western Christian Church appointed the night of April 30 to St. Walpurga’s Feast. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Walpurgisnacht was popularized and its witchy connotations were revived through the literature of the time, such as in Jacob Grimm’s work who wrote in 1833: “There is a mountain very high and bare… whereon it is given out that witches hold their dance on Walpurgis night”.

Goethe also dedicated a poem to the celebration called “Die erste Walpurgisnacht” (The First Walpurgis Night), which was set to music by Felix Mendelssohn and published as his Opus 60 in 1843. The poem contrasts sharply with the Walpurgisnacht described in his main work “Faust”. In his ballad, Goethe relates the superstitions around Walpurgis night to the usage of devil’s masks by pagan’s in order to exploit the superstitions of their Christian suppressors and to protect their identities. A short background story and a translation into English of the ballad including the music can be found here.

Frau Holle

Ernst Ludwig Rochholz, the Swiss historian and folklorist looks closely at the depictions of St. Walpurga and writes in his book “Drei Gaugöttinnen: Walburg, Verena und Gertrud als deutsche Kirchenheilige” (Three goddesses: Walburg, Verena and Gertrud as German church saints) from 1870:

“Nine nights before the first of May is Walburga in flight, unceasingly chased by wild ghosts and seeking a hiding place from village to village. People leave their windows open so she can be safe behind the cross-shaped windowpane struts from her roaring enemies. For this, she lays a little gold piece on the windowsill, and flees further. A farmer who saw her on her flight through the woods described her as a white lady with long flowing hair, a crown upon her head; her shoes were fiery gold, and in her hands she carried a three-cornered mirror that showed all the future, and a spindle, as does Berchta. A troop of white riders exerted themselves to capture her. So also another farmer saw her, whom she begged to hide her in a shock of grain. No sooner was she hidden than the riders rushed by overhead. The next morning the farmer found grains of gold instead of rye in his grain stook. Therefore, the saint is portrayed with a bundle of grain.”

This tale serves Walpurga’s depictions of holding a bunch of corn in one hand and the tradition of securing the barns during her intercession. But there’s more to this tale than just her patronage over peasantry. Her description is similar to that of a Germanic goddess. Such a Germanic goddess is Frau Holle, who Jacob Grimm revered as goddess Holda or Hulda, who may be the cognate of the Scandinavian forest creature Huldra.

“Holda, the good protectress”, by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, published in 1882. The Germanic goddess of witchcraft and protector of women’s crafts, is depicted in Germanic folklore flying through the air at night accompanied by the demonic spirits of men and women who left their bodies behind, which is reminiscent of the flight to the sabbath.

Frau Holda was associated with witchcraft, women’s crafts, and agriculture in the German folklore and similarly to Walpurga, the spindle was appointed to her as a symbol. The distaff, which resembles a broom, was also a symbol of Frau Holda. She was believed to ride on distaffs at night with her Hulden, the nocturnal spirits of the women who became her witches.

According to the Canon Episcopi quoted by Carlo Ginzburg in his “Ecstasies: Deciphering the witches’ sabbath” from 1990, the Hulden went “out through closed doors in the silence of the night, leaving their sleeping husbands behind” to go to feasts or battles in the sky. According to the Canon Episcopi, if a woman was accused of such a deed, she was required to do penance for a year.

Although Walpurga’s association with Holda is undeniable, there is evidence that points to yet another association, although it needs more exploration. A sibyl of the 2nd century AD from the Semnone tribe who was named Waluburg was in the service of the Praefectus Aegypti, as attested on an 11th century Greek ostracon from Egypt. Historians and archaeologists Camille Jullian and Théodore Reinach from the early 19th century wrote in 1920 a document titled “Une sorcière germaine aux bords du Nil” from “Revue des Études Anciennes” in which they talk about the inscription on the Greek ostracon from Egypt published by M. Schubart during the war in the Bulletin of the Museums of Berlin.

Weleda

Various texts attested the aid of divineresses in the military and political life of the Germanic people, such as this fragment from Dion Cassius that refers to the reign of Domitian: “Masyos, king of Semnons, and the virgin Ganna, who, after Véléda, had taken the role of prophetess in Germany, went to Domitian, who dismissed them after having filled them with honors”. The inscription on the ostracon names this divineress Βαλουβουργ (Valouvourg), which according to M. Schubart, transcribes to “Walburg” and undoubtedly evokes the night of the Walpurgis.

Waluburg’s name was also allegedly found on a list of Greek-Egyptian soldiers which is something that made many speculate on the origin of her name, as it may be connected to the Walkuren, who bring the slain on the battlefield to Odin in the afterlife. This further rises speculation on the etymology of Walpurgis.

Wal could mean “wand” and “chosen/corpse”, while purgis may stem from burg (homestead) or berg (mountain), which is further correlated with the rune Berkana, the rune of May, rebirth, nurture, creation, which evokes the Goddess’ motherly bond to her child. In this sense, Walpurgisnacht is a time of rebirth for nature, when the veil between worlds is thinner, and when the feminine power is at its peak.

Engraving from the 17th century by Michael Herr, depicting the events on the Blocksberg on Walpurgisnacht, accompanied by verse from the German poet Johann Klaj, warning against belief in witchcraft.

Jacob Grimm

Speaking of mountains and peaks, Jacob Grimm wrote in 1888: “The Witches’ excursion takes place on the first night in May… they ride up Blocksberg on the first of May, and in 12 days must dance the snow away; then Spring begins… Here they appear as elflike, godlike maids.” The Blocksberg that he refers to is also known as the Brocken and it is the highest peak of the Harz mountains in Northern Germany.

Various bizarre rock formations on the Blocksberg have such names as Teufelskanzel (the Devil’s Pulpit) and Hexenaltar (the Witch’s Altar). The mountain has been associated with witches since the 3rd century and it is likely that it used to be a site of ancient rites and celebrations. Legends say that witches flew on broomsticks from all over Germany to gather there and conjure magic, especially during the burning times.

Another legend says that Wotan married Freya on the Broken in Schierke, while other legends of devils and witches inhabiting the place were very prevalent due to the Brocken Spectre phenomenon which creates eerie optical illusions and gave raise to many superstitions, all of which inspired Goethe to write about it in his book, Faust.

Superstition and Tradition Throughout Europe

Engraving from 1829 by W. Jury, depicting the Walpurgis Night Scene from Goethe’s Faust.

Although flight to the Sabbath is no longer a tradition, Walpurgisnacht is still rich in superstitions and traditions. One of the more famous ones are the loud cheering and banging pots together that scare evil spirits and witches away, and the ritual bonfire, which people leap over, dance around, and which they use the purify and purge the year that passed, by throwing in the fire dolls made of straw that they imbue with all the misfortunes that may not befall them. Traditionally, women must also leap over their brooms, burn the old ones, and set a broom in the doorway to prevent evil witches from entering the house.

They also protect the cattle against evil witches, by hanging bells on the cows’ necks. Wearing a wild radish was also believed to protect against witches and evil spirits. As with any other such celebration, the Walpurgisnacht was a prosperous time for divination and love spells. If one slept with just a single sock on, they would wake up the next day to find a hair in it, the color of which predicted the color of the betrothed’s hair. A traditional divinatory love spell during the night suggests placing a linen thread next to a statue of Virgin Mary and unravel it at midnight as you say: “Thread, I pull thee; / Walpurga, I pray thee, / That thou show to me / What my husband’s like to be.”

Walpurgisnacht in modern day Erfurt, Germany. Nowadays, Walpurgisnacht is considered by some as the European Halloween, when people throughout Europe dress-up as witches and monsters, build a bonfire, and party in celebration of Spring. Walpurgisnacht is a public event that evokes the Sabbath of the Dark Ages and the fertility rites of Antiquity. Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/michael-panse-mdl/6985387308/

Variants of the Walpurgisnacht celebrated in Germany can be found throughout Europe in the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Sweden, Finland, and more. In Czech Republic, the night of April 30 is known as pálení čarodějnic (burning of the witches) or Valpuržina noc, while May 1 is the Day of Love. It is celebrated by young people who gather on top of the hills around bonfires where they create effigies of witches and throw them in the fire.

In Estonia, it is known as Volbriöö, and it is celebrated from the night of April 30 when people dress up as witches, into the day of May 1, when Estonians celebrate Spring Day. In Finland people celebrate it as Vappen, while in Sweden people celebrate it as Valborg, which marks the arrival of Spring, and both celebrations are revered as important public events. In Sweden, people light bonfires, they dress up, dance, and sing in the celebration of spring.

It seems that a large part of Europe celebrates its own version of Walpurgisnacht as a traditional welcoming of spring and renewal, which just like Beltane, originates in an ancient celebration of fertility. Fire and feminine power seem to be at the core of these celebrations. The first of May which follows the Walpurgisnacht, although now celebrated by all as International Worker’s Day, is a time of peace, serenity, and recreation on a spiritual level for many.

Walpurgisnacht has truly become a traditional night when witches celebrate their magic, either by participating in the public events that evoke the old days or by gathering in private. On this note, I’ll conclude with a few verses from “Die erste Walpurgisnacht”: “As the flame is purified by smoke, so purify our faith / And even if they rob us of our ancient ritual, / who can take your light from us?”

www.Nettlesgarden.com – The Old Craft

Mark A. O'Blazney | May 1, 2018

|

+

Angela | April 9, 2019

|

Excellent Sister ❤️??♀️